[The following article is reprinted by permission of the New England Historic Genealogical Society. The article originally appeared in the Winter 2023 edition of AMERICAN ANCESTORS on pages 27-31. For more information about AMERICAN ANCESTORS magazine and the New England Historic Genealogical Society, please visit AmericanAncestors.org.]

On September 1, 1702, a man named Abraham Coriell registered a cattle mark in Piscataway Township, Middlesex County, New Jersey. Aside from that modest record, Abraham left only a trace in local annals, and subsequent research by his descendants revealed little more about him over the following three centuries.

Through genetic genealogy, we learned something significant about Abraham Coriell: he was descended from the Curiels, a notable Sephardic Jewish family that suffered forced religious conversion and persecution during the Inquisition. The family later found refuge in Amsterdam, Hamburg, Italy, and the Ottoman Empire, where they achieved great wealth and social prominence.

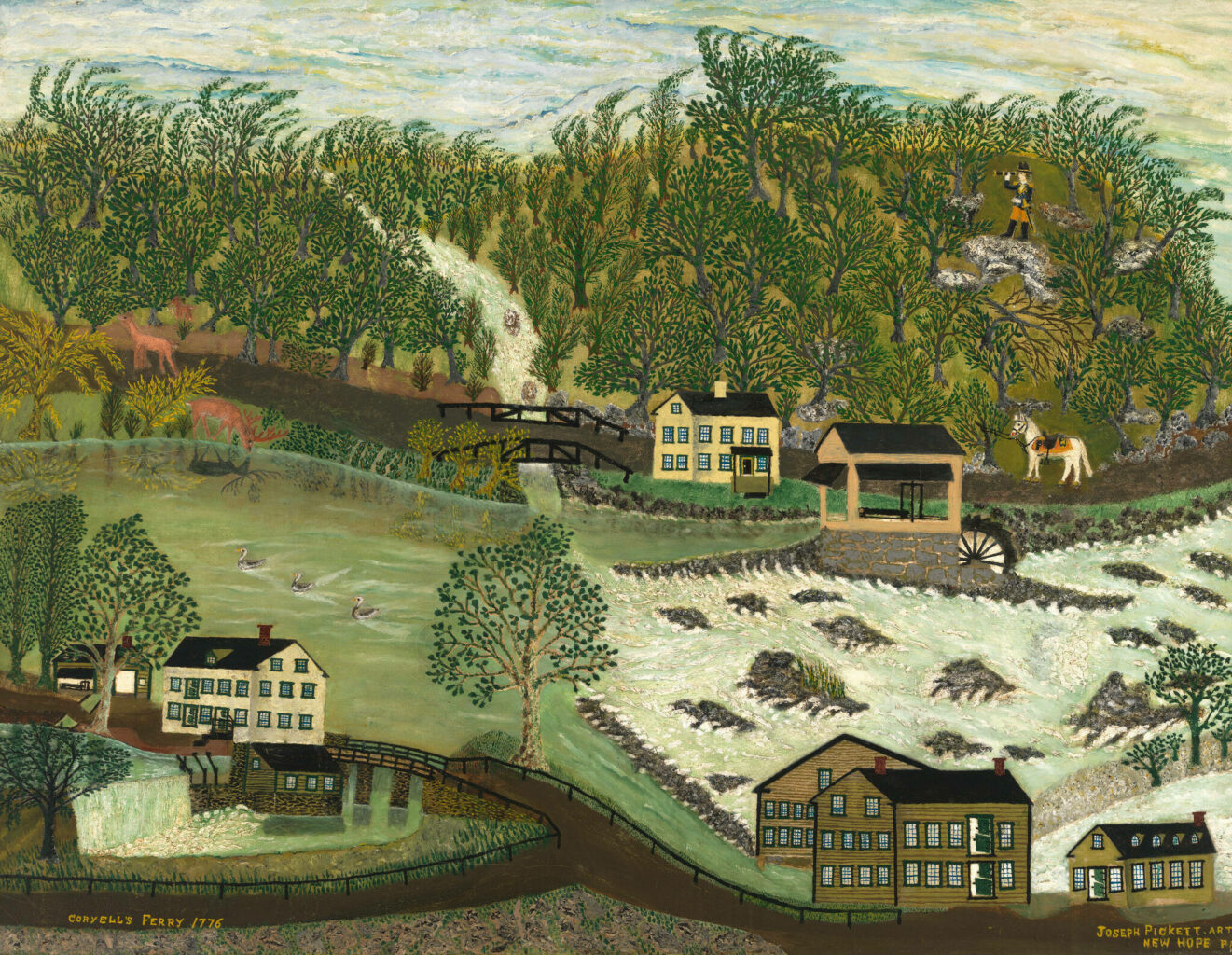

Abraham Coriell himself was the progenitor of an extensive American family. His grandsons operated a ferry across the Delaware—Coryell’s Ferry—which played a strategic role during the Revolution. More than a dozen Coryell men from New Jersey fought with General George Washington, earning Washington’s long-lasting friendship and respect. One of them later served as his pallbearer. Another descendant was captured by the British and reportedly died aboard a prison ship in New York harbor. Abraham’s great-grandson, Abraham Coriell, a father of ten, was killed in action while fighting in the War of 1812. Another descendant, James Coryell, served as a Texas Ranger and, in 1837, was scalped by Caddo Indians while raiding a bee tree. 1 Texas named a county in his honor. Many more of Abraham’s progeny served in the Civil War.

The Sephardic ancestry of this quintessential American family would have remained unknown had it not been for a collaboration between Lea Coryell, an American genealogist tracing his family history, and the Avotaynu Project, a multi-disciplinary academic study that has been DNA-testing thousands of Jews worldwide in search of genetic echoes of their origins and migrations.

The Coryells: Tracing an American family’s roots

“The most prevalent idea,” Coryell family historian Ingham Coryell (1906–1986) once wrote, “is that the Coryells were French Huguenots.” 2 Based on family lore first published in nineteenth-century local histories, this belief persisted despite the absence of any corroborating primary source documents. In 1981, James W. Thompson wrote a letter to the now-discontinued family Coryell Newsletter challenging the Huguenot connection:

In Amsterdam . . . there was a family of Sephardic Jews named Curiel, in which family the names Abraham, David, and Moses all appear. Are they our ancestors? I believe that a good expert in Dutch records could find some remarkable things on this point. 3

After receiving spirited criticism from relatives who clung to the French Protestant connection, Thompson pursued the matter no further. This search was not resumed until four decades later, when Lea Coryell recognized that advances in genetic genealogy might help solve the mystery of his family’s origins.

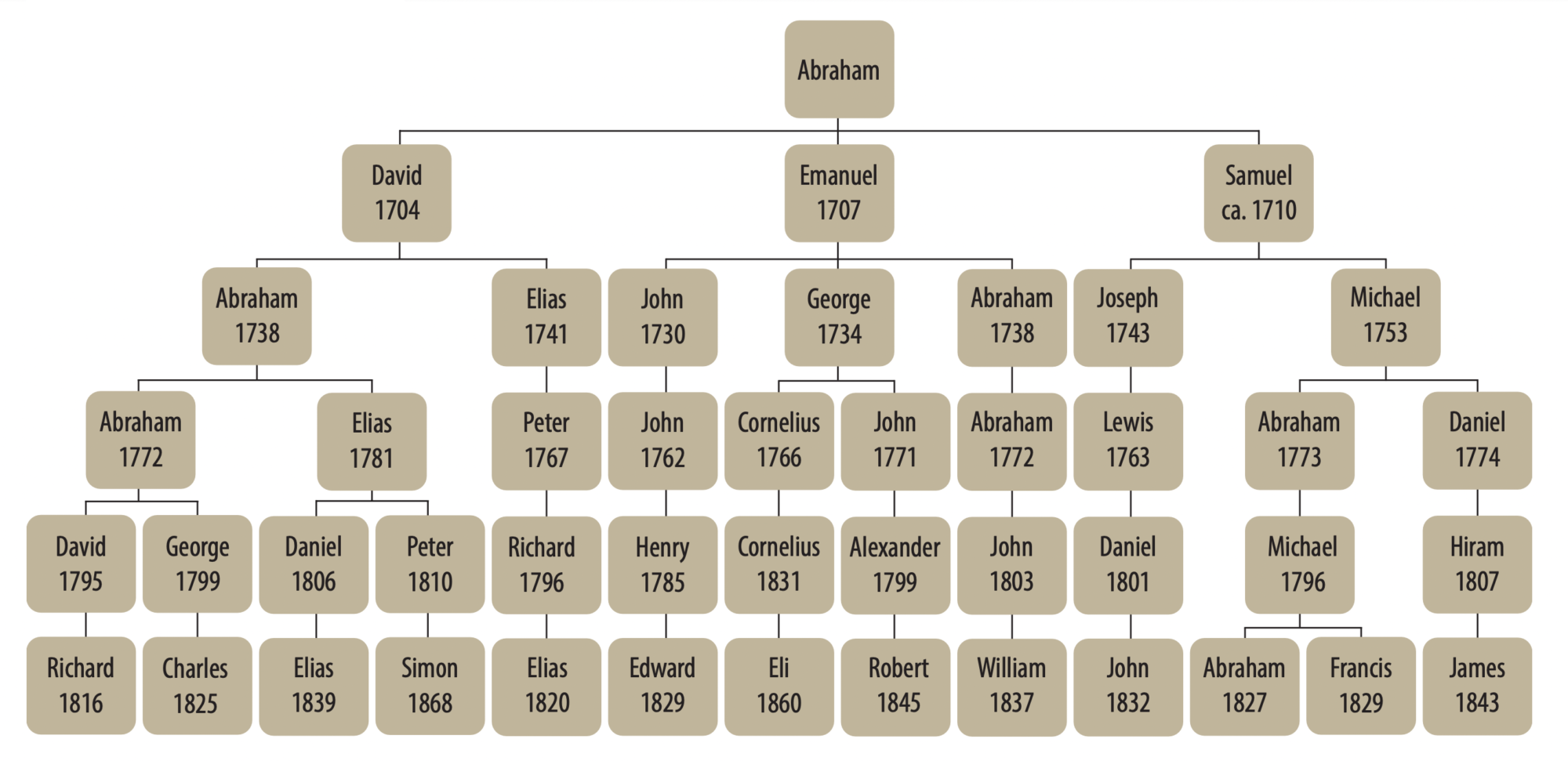

In 2009, Lea formed the Correll/Coryell Y-DNA Project. Through variations in the Y chromosome unique to Coryell descendants, he sought to confirm a hypothesis first offered by Coryell family historian Emma Finney Welch (1855–1926). Welch believed that Abraham fathered four Coryell sons who appeared in eighteenth-century New Jersey records: David (1704–1779), Emanuel (1707– 1749), Abraham, and Samuel (d. 1760). In 1979, Noble Burr Coryell (1917–2006), editor of the Coryell Newsletter, wrote that the “ultimate goal” for him and his fellow descendants was to trace their lineage back to Abraham through one of those four sons. The DNA revolution would provide the tools.

Lea recruited thirteen male descendants of David, Emanuel, and Samuel and tested their Y-DNA. Sequencing by FamilyTreeDNA revealed that all thirteen share a genetic variation on the Y chromosome known as E-BY145801. The discovery of the shared variation helped pinpoint Abraham’s origins, supported the theory that David, Emanuel, and Samuel were his sons (their brother Abraham has no known living descendants), and led to the identification of additional genetic variations that would distinguish different Coryell lineages. The Coryell Project (familytreedna.com/groups/correll) currently includes 34 participants bearing the surnames Coryell, Coriell, Correll, or Corell who have provided Y-DNA samples (28 at the Big Y level), as well as men with different surnames who have matching Y-DNA signatures. Throughout the process of Big Y DNA testing, all new variations have been cataloged so that future Coryell participants and their genetic matches will find a place on a shared family tree.

The Curiels: Tracing the fate of Iberia’s Jews

While Lea pursued his investigation of the Coryells, the Avotaynu DNA Project began exploring the origins and migrations of the Jewish people in 2016. One study focused on the known descendants of the Jews of Iberia whose persecution included anti-Jewish massacres in Spain in 1391, expulsion from Spain in 1492, and forced conversion of all Portuguese Jews in 1497. To recruit study participants, a team of academics and community historians scoured Jewish communities with known Sephardi descendants, concentrating on the Iberian Jewish diaspora in Curaçao, Amsterdam, London, Italy, Turkey, Syria, and North Africa, as well as the early Sephardi families of colonial America.4

Fortuitously, the Avotaynu study volunteers from Curaçao included a descendant of the Curiel family of Amsterdam and Hamburg, among the most venerable families in the Jewish world. His Y-DNA results closely matched those of the American Coryells. The Curiel line apparently descends from an as-yet-unidentified progenitor who converted to Christianity under duress in Portugal in 1497. That man’s son, Dr. Fernão Lourenco (a physician born about 1494 in Coimbra, Portugal), and his grandson, Duarte Nunes (a wealthy cloth merchant born about 1525, also in Coimbra), are the earliest known members of the family.

Duarte’s children are described in a 1676 genealogical manuscript now held in the Ets Haim (Tree of Life) Library in the Portuguese Synagogue (Esnoga) in Amsterdam. According to the manuscript, Duarte Nunes had ten children. 5

The divergent life paths of Duarte’s children are evident in this single generation. While the Portuguese Inquisition courts persecuted several of Duarte’s children, his son Francisco de Vitoria became an influential bishop of the Spanish Empire. Two other sons, Fernão Lourenco Ramires and Diogo Peres da Costa, returned to Judaism in the Ottoman Empire, where they adopted the names Abraham and Jacob Curiel. Their elder brother, Dr. Jeronimo Nunes Ramires (1545–1609), remained in Portugal, while his two sons, Lopo Ramires and Duarte Nunes da Costa, returned to Judaism and adopted the names David and Jacob Curiel before settling in Amsterdam/Rotterdam and Hamburg, respectively. To our knowledge, the adoption of the name Curiel by the two brothers and their two nephews was the first use of the surname in the family.

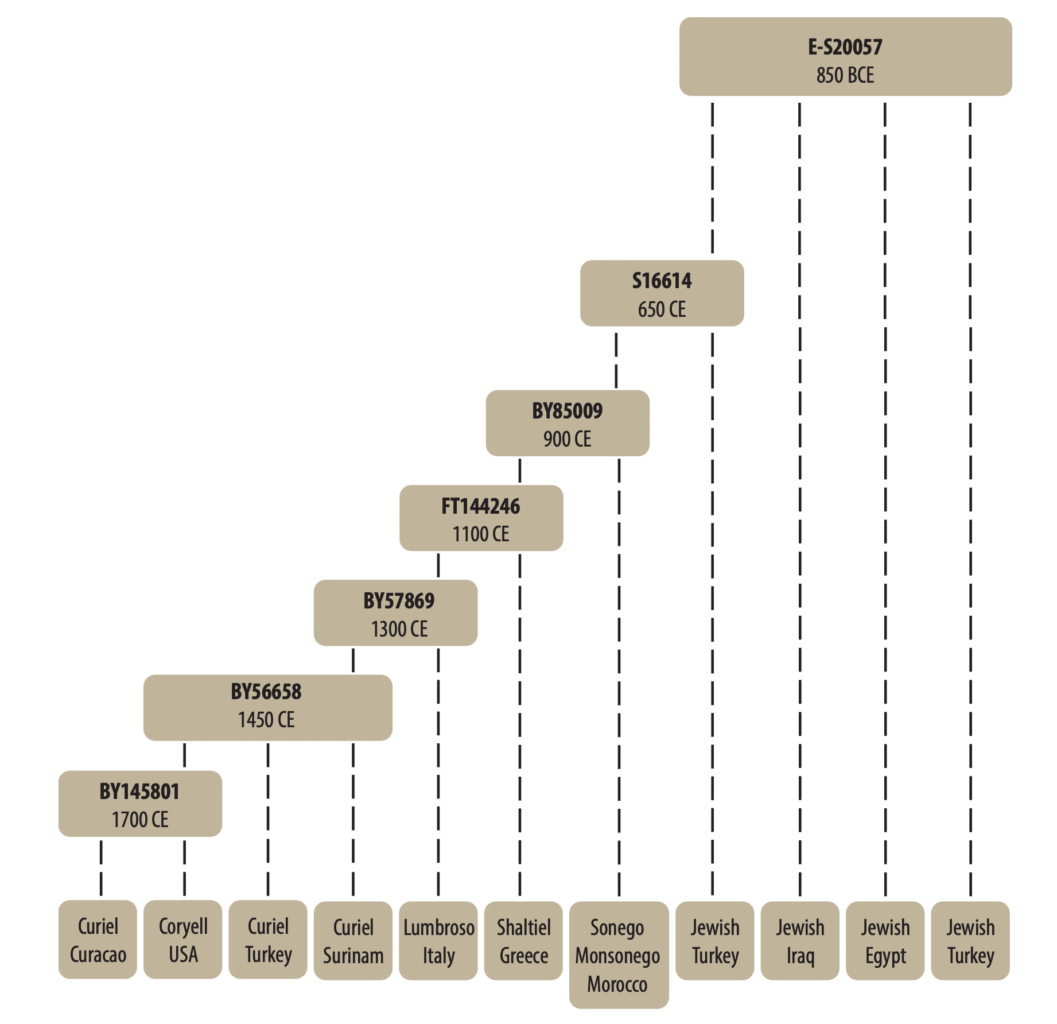

We were fortunate to recruit verified Caribbean descendants from each of Jeronimo’s adult sons and a third individual from Izmir, who appears to descend from one of Jeronimo’s brothers who had settled in the Ottoman Empire. All three participants and, by extension, their common ancestor Duarte Nunes (b. 1525) share a common Y-DNA variation, designated E-BY56658. One of the three recruits, a Curiel from Curaçao and a descendant of Jacob Curiel of Hamburg, carried an additional genetic variation that was not present in the others, E-BY145801. As noted above, this variation is shared by the Coryell family in America and confirms that the Coryells are Jacob Curiel’s descendants. This discovery led to the collaboration between Lea Coryell and the Avotaynu project.

the man on the left distributing matzah, a role for the individual designated to lead the annual Passover seder. The Passover of the Portuguese Jews,

engraved by Bernard Picart, is from Jean Frederic Bernard and Bernard Picart, Religious Ceremonies of the World (Amsterdam: 1723). Wikimedia

Commons.

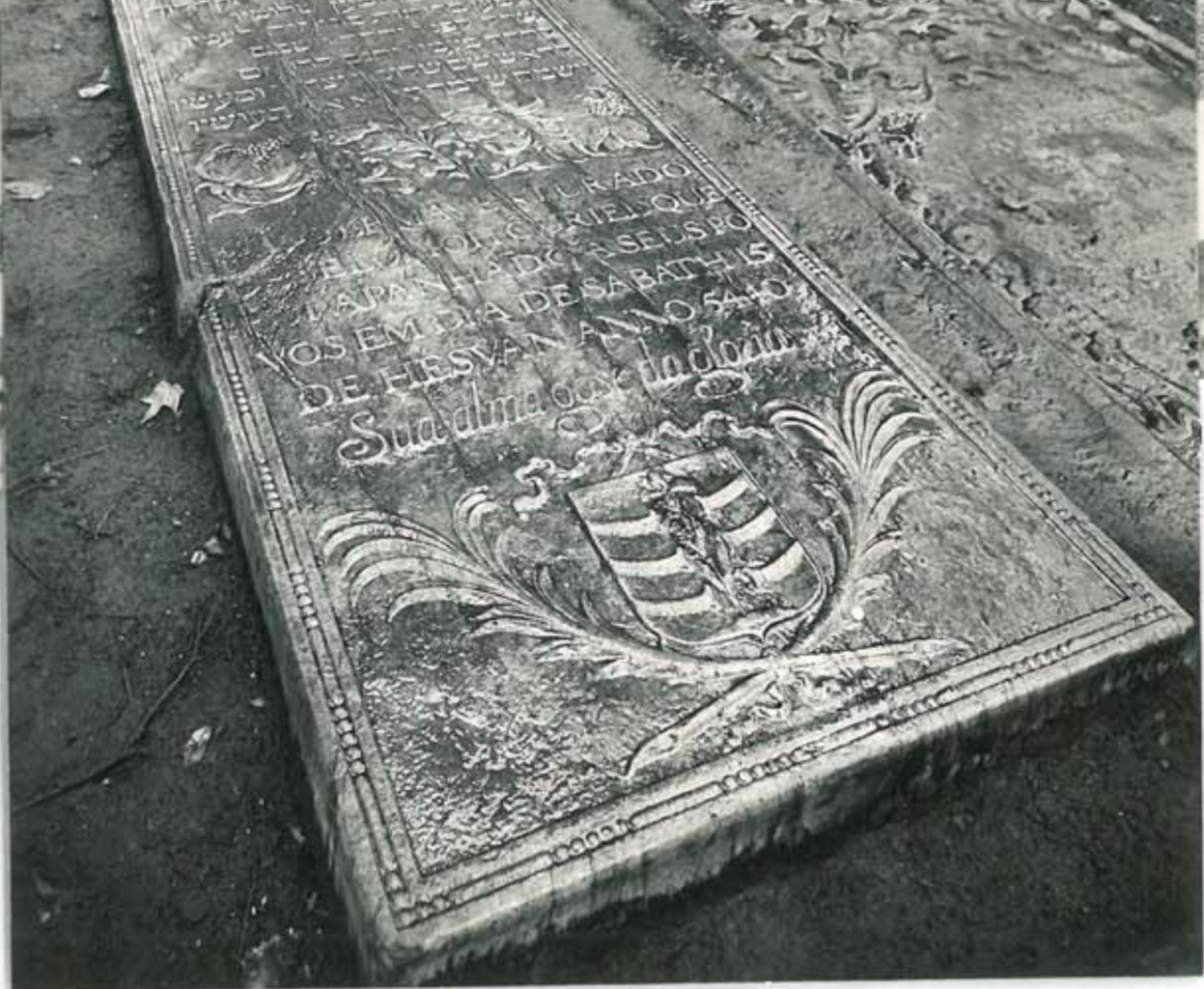

Jacob Curiel was born in Coimbra, Portugal, on September 26, 1587, as Duarte Nunes da Costa. He eventually oversaw a family trading empire that dealt in such far-flung products as Brazilian sugar and Indian diamonds. Fleeing Portugal one step ahead of the Inquisition, he eventually landed in Hamburg. He became a major arms supplier to Portugal during the civil war that followed its 1640 secession from Spain, advancing personal funds to keep the gunpowder and weapons flowing. The Portuguese crown rewarded him with an official office as its representative in Germany. In 1641, Jacob was knighted by King João IV, becoming a cavalier fidalgo and receiving a coat of arms. His rise to prominence was a remarkable turn of events for a man who had fled Portugal in fear of his life and burned in effigy by the Inquisition in Lisbon.

Although Jacob never stepped foot in the Americas, he played a role in American history. He was one of the largest shareholders of the Dutch West India Company, which in 1654 forced Peter Stuyvesant, its agent in New Amsterdam, to admit two dozen Jews who had been diverted there as they tried to flee from South America to Holland. A decade later, Jacob Curiel died at age 76 on April 3, 1664, in Hamburg.

We know from the unique E-BY145801 variation that Jacob was an ancestor of Abraham Coriell of New Jersey, but the intervening generations are unknown. Given the Curiel family history, the intervening generations might well have included gentile women. Jacob’s brother David apparently fathered children out of wedlock, as the Portuguese Jewish communities in northern Europe had more than their fair share of men crossing social boundaries and having children with non-Jewish women.

Notwithstanding the missing generations between the American Coryells and the Curiel dynasty, and the unknown identity of the Curiel ancestor who was forcibly converted to Christianity in 1497, the ancient Jewish origins of the Coryell line are incontrovertible. Among the participants in the Avotaynu study are men from documented Sephardic Jewish families such as Lumbroso (from Italy), Shaltiel (from Thessaloniki, Greece), and the Sonego/ Monsonego rabbinic dynasty (from Morocco). Our dating suggests that they share common paternal ancestry with the Curiels dating back to the medieval era. Matches with Jewish participants from Egypt, Syria, and Turkey reveal a common ancestor who lived at the time of the birth of apparent Israelite identity in the Early Iron Age, as shown.

When Lea Coryell set out to explore his ancestry, he discovered not Huguenots, as many relatives expected, but an extensive Jewish family tree with ancient roots and branches that included seventeenth-century trading moguls and a Moroccan rabbinic dynasty. When the Avotaynu DNA Project sought the descendants of a Jewish man forced to convert to Christianity in Lisbon in 1497, the researchers were surprised to find close associates of America’s Founding Fathers and even a Texas Ranger. The search for the Coryell ancestry exemplifies not only the power and promise of genetic genealogy, but also the vital role of collaboration and open minds.

For further information about the Avotaynu DNA project, please contact co-author Adam Brown at AvotaynuOnline@gmail.com.

NOTES

- Carolyn Hyman and Toni S. Turner, “Coryell, James,” Handbook of Texas Online, tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/coryell-james.

- Ingham Coryell, Emanuel Coryell of Lambertville, New Jersey and his Descendants (Philadelphia: the author, 1943), 5.

- James W. Thompson, “Letter Worth Sharing,” Coryell Newsletter, 15 (November 1981), 4.

- For further information about the Avotaynu DNA Project, see AvotaynuOnline.com.

- Jonathan I. Israel, “Duarte Nunes da Costa (Jacob Curiel) of Hamburg, Sephardi Nobleman and Communal Leader (1585–1664),” Studia Rosenthaliana 21, no. 1 (May 1987), 14–34.

The Coddington-Coryells (I-FT357299)

Our study discovered a previously unknown misattributed parentage that resulted in David A. Coryell (1758–1835) of Bernards Twp., New Jersey, putatively the great-grandson of founder Abraham Coriell, carrying an entirely unrelated Y-DNA variation, I-FT357299. David appears to have inherited this variation from a member of the Coddington family of Woodbridge Twp., N.J. Coauthor Lea Coryell’s brick wall ancestor Richard F. Coryell (1794–1845) of Warren Twp., N.J., shared this variation, and we believe Richard F. was David A. Coryell’s son. Notwithstanding this newly uncovered Y-DNA mismatch between David A. Coryell and his putative father and younger brothers, David passed the Coryell surname on to Lea and hundreds of other descendants.