Leipzig is one of the oldest trading cities in the world and its Trade Fair (Germ. Leipziger Messe) is one of the oldest Trade Fairs in the world. Leipzig was at the crossroads of two important trade routes: Via Regia [Royal Highway], running through the center of the Holy Roman Empire from Paris to Novgorod, and Via Imperii [Imperial Road], connecting Venice with the Baltic coast. In 1497, Maximilian I (who became Emperor in 1508) granted the city imperial trade fair privileges, an advantage that led to the city’s recognition as an origin of international trade fair operations.

The city’s central location attracted Jewish traders from all over Europe to the Leipzig Trade Fair, an important event that cultivated foreign relations among European nations and served as a meeting place for politicians. There were three fairs annually: the New Year’s Fair, which began on 1 January; the Easter Fair, which began in April or May; and St Michael’s Fair, which began around 29 September. The latter two fairs attracted most visitors. Jews played a central role at the fairs. At the Easter Fair of 1756, for example, about 16 percent of the visitors were Jewish. Local merchants feared the Jewish competition. As a result, Jews were not allowed to remain in Leipzig after the fair and they had to pay a special body tax (Germ. Leibzoll) to enter the city.

Even though they had to pay special Leibzoll body taxes, close to 82,000 Jews from all over Europe are estimated to have attended the Leipzig fairs between 1688 and 1764. The fact that they contributed 719, 661 Reichsthalers to the city coffers for this privilege made their presence particularly appreciated.1 The Trade Fair regulations of 1268 reflected this as well, as Jewish merchants were granted rights equal to the rights enjoyed by Christian merchants, and the market day was changed from Saturday to Friday in respect for the Jewish Sabbath.2

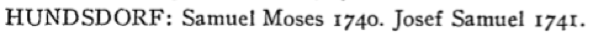

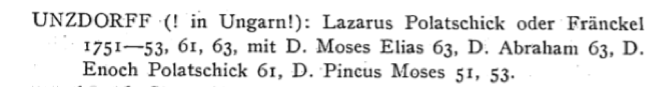

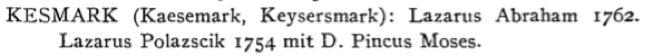

Lists of Jews who paid the tax have been preserved from 1675 to 1764. Max Freudenthal published the names of Jews who attended the fair.2 Using the Slovakian village of Huncovce as an example, this article illustrates the use of Freudenthal’s book in genealogical research.

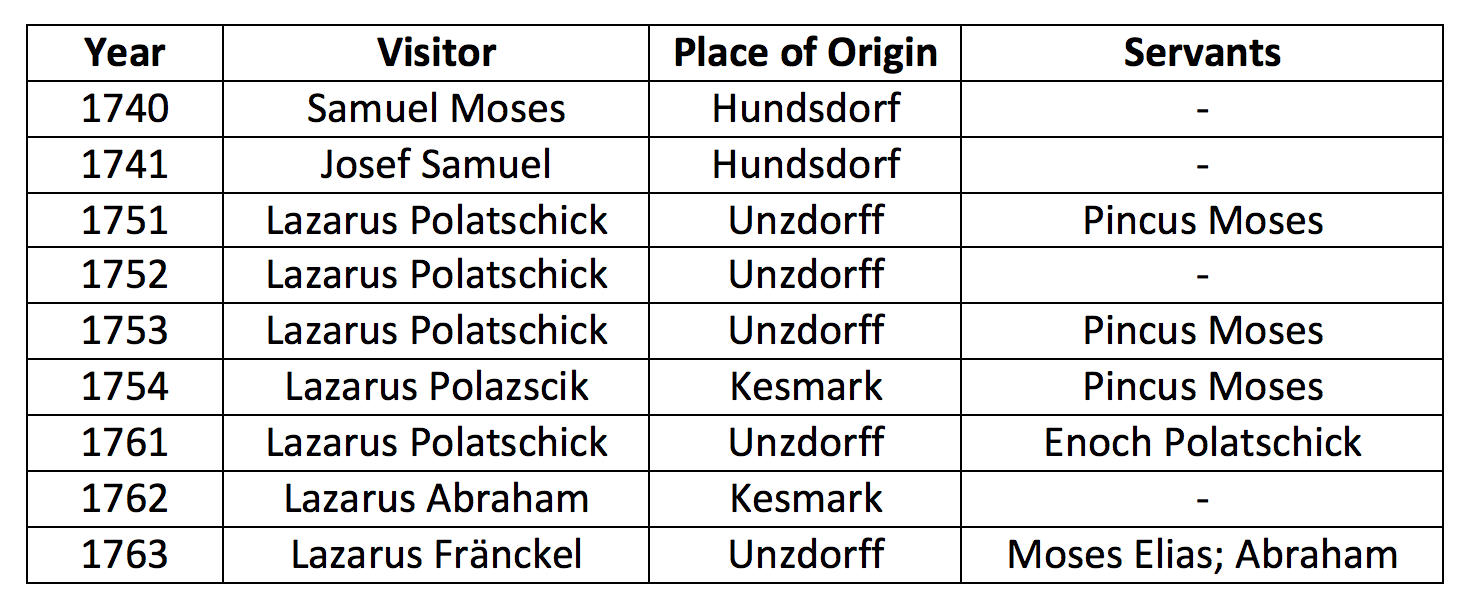

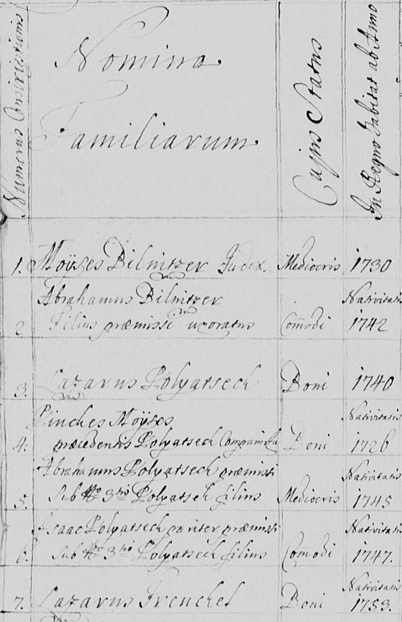

Before 1840, Jews were excluded from certain Hungarian cities, such as the Slovakian town of Kežmarok (Hung. Késmárk). Therefore Jews often lived in nearby villages, Huncovce (Hung. Hunfalu; Germ. Hunsdorf) in the case of Kežmarok. Table 1 presents the list of visitors from Huncovce and Kežmarok, which we have adapted from Freudenthal’s book (see Figures 1-3).

There are five different names of visitors. Our analysis suggests that these names only represent four different visitors. Using additional sources, we will try to show that three of the four visitors and two of the four servants belong to the same family business, spanning three generations.

It is an irony that we know the names of Jewish ancestors who visited the fair as a result of discrimination against Jews. To find out more about the visitors, who often came “with servants” (Freudenthal: “mit D.”), we consulted two Hungarian sources, which also are the result of discrimination against Jews: the Conscriptio Judaeorum, which was a census of Jewish households; and the tolerance tax lists (Germ. Toleranzgebührer). We will discuss the visitors and their servants in chronological order.

Samuel Moses: He visited the fair in 1740 from Hundsdorf (in the county of Szepes). The 1736 census of the county of Szepes mentions him as Samuel Mojsis.3 Samuel is the first on the list of eight households. The 1746 census of Huntzdorff does not mention him anymore. Before 1736, Samuel may have lived elsewhere in Slovakia, because Freudenthal mentions a visitor from Hucina (Heczina) by the name of Samuel Moses in 1726.4

Josef Samuel: He visited the fair in 1741 from Hundsdorf. The 1746 census of Huntzdorff mentions him as Josephus Samuel.5 If Samuel is a patronymic, then he is likely to have been a son of Samuel Moses. If this is correct, then he continued the business of his father. The 1746 census also mentions Josef’s daughter Ester and son-in-law Pinkus Mojses. Pinkus is listed in the same line as his father-in-law, suggesting that they were living in the same house. Below, we will return to this son-in-law, because he is our link to the next generation.

Lazarus Polatschick: He visited the fair in 1751-54 and again in 1761, three times with his servant Pincus Moses. The 1768 census of Hunsdorff mentions Lazar and Pinkes (in Latin: “Lazar et Pinkes”).6 Together they head the third household in the census. No family name or patronymic is provided for the two. These must be Lazarus Polatschick and his “servant” Pincus Moses. Pincus was the son-in-law of Josef Samuel (see above). Thus, Lazar and Pinkes continued Josef’s business. The 1771 census of Huntzdorff lists the year of birth for Hungarian Jews and the year of immigration for foreign Jews (see Figure 4).7 Lazarus Polyatseck, who immigrated in 1740, is third on the list. Pinches Moijses, who was born in Hungary in 1726, is fourth on the list. Fifth and sixth are two sons of Lazarus (“sub No. 3tio Polyatseck filius”): Abrahamus (born 1745) and Isaac (born 1747). The entry of Pincus between those of Lazarus and his two sons, suggests that he was more than just a business partner. Being a business partner of Pinches Moijses (in 1771) and living in the same household as Pinkes (in 1768) strongly suggests that Lazarus also was a son-in-law of Josef Samuel. We were unable to determine the exact family relationship of Lazarus with his “servant” Enoch Polatschick.

In 1754, Lazarus Polazscik and Pincus Moses claimed to have come from Kežmarok. However, Jews were not allowed to live there at the time. The 1746 and 1768 censuses confirm that they lived in Huncovce.

The 1771 census explicitly calls Pinches Moijses a (business) partner of Lazarus (in Latin: “praecedentis Polyatseck companista”). Moreover, Pinches Moijses and Lazarus Polyatseck are both listed in the 1771 census as being of good social status (in Latin: “Boni”). However, Pincus Moses visited the fair as a servant of Lazarus Polatschick! Freudenthal (page 19) explains that business partners and relatives often posed as servants, in order to benefit from a lower tax rate.

Lazarus Abraham: Lazarus Abraham visited the fair in 1762 from Kežmarok. Probably he came from Huncovce, because Jews were not allowed to live there. The 1746 census is the only one to mention him. We propose to identify Lazarus Abraham with Lazarus Polatschick. Lazarus Polyaczek is mentioned in a document from 1745.8 Thus, the 1746 census should have mentioned him. Instead, we find Lazarus Abraham. His patronymic suggests that he was a son of Abraham Polyacsek. The fact that Lazarus Polyaczek had a son by the name of Abraham (born 1745), also supports the identification of Abraham Polyacsek as the father of Lazarus. Abraham Polyaczek is No. 7 in the 1736 census.

There are two problems, however, with the identification of the older Abraham as the father of Lazarus and the grandfather of the younger Abraham. First, in 1771 the younger Abraham claimed to have been born in 1745, whereas in 1746 the older Abraham was still alive. Second, in 1771 Lazarus claimed to have immigrated in 1740, whereas the older Abraham is already mentioned in the census of 1736. However, retrospective information is often inaccurate. The best-known example is age overstatement.9 Thus, the younger Abraham may actually have been born in 1746, whereas his father Lazarus may have immigrated in 1736. The family name Polatschick (i.e. little Pole) suggests that the family came from Poland.

The 1774 and 1782 census mention Lazar Polyarcsek. The tolerance tax lists mention him for three consecutive years in 1786/87, 1787/88, and 1788/89. The 1789/90 tax list does not mention him anymore.10

Lazarus Fränckel: Lazar Frenkel is No. 2 in the 1768 census, before Lazar [Polatschick] and Pinkes [Moses], who are listed together as No. 3. Lazarus Frenckel is No. 7 in the 1771 census, immediately after the two sons of Lazarus Polyatseck. We failed to find any evidence for a family or business relationship between Lazarus Polatschick and Lazarus Fränckel. Freudenthal thought that they were one and the same person, making it difficult to determine in which year they visited the fair, without inspecting the original documents (see Figure 2). Fortunately, four times the name of the “servant” (Pincus Moses and Enoch Polatschick) enabled us to determine the identity of the visitor. This leaves 1752 and 1763 as the only two years, in which it is unclear which of the two visited the fair. The 1771 census gives his year of immigration as 1753. If this year is accurate, then Lazarus Fränckel is unlikely to have visited the fair in 1752 from Huncovce, leaving 1763 as the only year. We have not been able to identify the “servants” of Lazarus Fränckel.

The 1774 and 1782 census mention Lazar Frenkel. The tolerance tax lists only mention him once, in 1786/87.

All the visitors were already known to us from other contemporary sources. However, the list of visitors to the fair at Leipzig tied three of the four visitors together in what appears to have been a family business spanning three generations. Unfortunately, we do not know in what commodities the family traded. It is possible that there also were visitors from the same family to the fair in Leipzig in the fourth generation. However, the list stops in 1764.

Endnotes

1. Robert Allen Willingham II, “Jews in Leipzig: Nationality and Community in the 20th Century”, dissertation, the University of Texas at Austin, 2005, page 16. Downloaded at https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/bitstream/handle/2152/1799/willinghamr73843.pdf.

2. “The Jewish Community of Leipzig”, https://dbs.bh.org.il/place/leipzig.

2. M. Freudenthal, Leipziger Messgäste: Die Jüdischen Besucher der Leipziger Messen in den Jahren 1675 bis 1764 (Frankfurt am Main: J. Kauffmann Verlag, 1928). Download at http://sammlungen.ub.uni-frankfurt.de/urn/urn:nbn:de:hebis:30-180015189004.

3. Monumenta Hungariae Judaica XVII, page 252. The census does not mention place names.

4. Freudenthal, page 141. Hucina may be Hucín (German: Hutzendorf; Hungarian: Gice or Gizce).

5. Monumenta Hungariae Judaica VII, page 800.

6. Monumenta Hungariae Judaica XVI, page 266.

7. LDS film #1529696.

8. Monumenta Hungariae Judaica VII, page 707.

9. Jona Schellekens (1995), “Age overstatement among European Jews”, Avotaynu XI, pp. 30-31.

10. We consulted www.jewishgen.org for the 1774 and 1782 census and the tolerance tax lists.