When he was 50, my husband, Nahum Gedalia, who was born in Belgrade, Yugoslavia, in 1948 and had not previously shown any interest in his genealogy or family history, asked me for a family tree. Having no living family members to interview, all I knew was that his paternal Sephardic family had come from a town called Nis in Serbia and that all ancestors and descendants, but for his father, perished in 1942.1 I had no idea then that the research would take me back to a Portuguese family that arrived in Salonika with a large group of Jews in 1505. This is the story of how I traced his family, mostly from books and with few archival records.

[This article was first published in the Summer 2016 edition of AVOTAYNU, The International Review of Jewish Genealogy and was based on a lecture at the IAJGS Conference Seattle 2016. To obtain a subscription to AVOTAYNU, please visit https://www.avotaynu.com/journal.htm – Ed.]

One must always start any Jewish genealogical research with the etymology of the family name and with a location’s history. I started with the Gedalia surname. Gedalia/Guedalia is a Biblical Sephardic name that appears in several books, among them Notable Families Among the Sephardic Jews, by Isaac da Costa, Bertram Brewster and Cecil Roth.2 It also appears in the article “Aliases in Amsterdam,” by Viberke Olsen,3 and many more resources listed on the JewishGen Sephardic Special Interest Group (SIG) site. In Hebrew, Gedalia means Great Lord and it used to be, and still is, a given name. Thus, we genealogists call it a patronymic name—a surname derived from a paternal given name. (For the most prominent Gedalia public figure, see Tzom Gedalia.)4

As it is crucial to put the family in the right historical place and context, such as the regime and its ruling governmental system, I went back to books5 and learned about the Nis Sephardic community, which was extremely loyal to the Ottoman Empire.

Next, I looked for a Jewish Serbian historian and found the well-known Ms. Zeni Lebl. Lebl was the one who told me about Rabbi Rachmim Naftaly/Nehemia Gedalja, who was summoned to be a chief rabbi in Nis in 1756 and whose tombstone reads Harav ha Kolel shel Nis. Niftar le’olamo yud Tet tishreri 5541. (“The all-inclusive rabbi of Nis. passed away October 18, 1780.”) Although the stone can be seen in a photograph taken 50 or more years ago, it will not be found on a visit today. The Jewish cemetery was expropriated by the Communist authorities in 1948 and burials were barred in 1965. After that, Roma families occupied one-third of the site, building homes among the tombstones and creating a “village,” while using the stones as building materials and for furniture. Although the cemetery was cleaned a few years ago by a large national and international task force that recovered and restored many stones, Rabbi Gedalja’s tombstone was not recovered.

Lebl also told me the story of Jewish Nis, citing the book she wrote, The Jews of Serbia.6 Subsequently, I have learned that Nis was one of the oldest cities in the Balkans and served as an east-west connecting passage. The city was named after the Nisava River, which flows through it. Over the years, it was also called Navissos by the Celtics in the third century BCE, Naissus by the Romans, Nysos by the Byzantines and Nis by the Slavs. Constantine the Great, the first Christian emperor, was born there.

In 1375, the Ottoman Turks captured Nis for the first time. The second time Nis succumbed to Ottoman rule was in 1448, and it remained under Sanjak Rule for the following 241 years.

The first recorded mention of the Sephardic Jewish community in Nis is from 1651 when Jews were given land of their own. The Hebrew word Nachala appears in old documents, but I have learned that it actually should read machlessi, which means “neighborhood” in Turkish. Nis was taken from the Turks by the Serbian army in 1878 during the Ottoman-Serbian War (1876–78).

According to Yad Vashem’s Pinkas Hakehilot,7Nis was a typical homogeneous Sephardic community of Jews expelled from the Iberian Peninsula who migrated there from the Balkan southern areas of the Ottoman Empire starting in the 17th century.

Lebl’s chronicles, translated for me by my husband, left me with a few questions. From where had Rabbi Rachmim Gedalia been summoned to Nis? Before he was summoned in 1756, the rabbi of Nis had come either from Belgrade or from Sofia, Bulgaria.8 How—if at all—was my husband related to Rabbi Gedalia? Are there people in this community today who can help me with my research?

I Googled “Nis Jewish community” and was surprised to find Jasmina (Jasna) Ciric9 since the family had never mentioned that there still was a Jewish community there. Jasmina proved to be another major source of information about the town.10 She cited the “common belief” in Nis that Rabbi Rachmim Naftaly/ Nehemia (both names came up in her stories) was a descendant of Don Yeuda Gedalia who arrived from Lisbon, Portugal, and in

1505 was the first Hebrew printer in Salonika.11 Now I had three towns on my research map, Lisbon, Nis, and Salonika, but I had no identified migration paths.

The research needed a plan and once again I needed to go back to the books to learn about topics of which I knew little—the Portuguese Jewish community and its waves of migration, the Sephardic Jews in Salonika, rabbinic genealogy and Hebrew printing. As I dove deeper into my research, I had more Sephardic communities and subjects to explore.

I based my research plan on two basic elements. Assuming that most Gedalias may be related,12 such as the Albohers, Aramas, Kobos, Shealtiels, Toledanos, Versanos and other Sephardic clans, I decided to map all Sephardic Gedalias.13 The second significant element is the Sephardic naming pattern in which a baby is named in honor of a grandparent who is still alive (unlike the tradition of the Ashkenazim). Therefore, I needed to look for another Rachamim Naftaly/ Nehemia Gedalia among the other branches.

Mapping the Gedalias from Nis was my first step. I started by using Yad Vashem Pages of Testimony submitted by my father-in-law and others, aggregating lists from Lebl’s and other books and mapping the cemetery. I made a roots trip to Serbia where I was introduced by Jasna Ciric to “lost” relatives I had never before heard of, children and grandchildren of Pesha Gedalia, my father-in-law’s first cousin who returned to Nis after five years of captivity in Germany. This enabled me to make an attempt to build a tree, which started with my husband and went back in time.

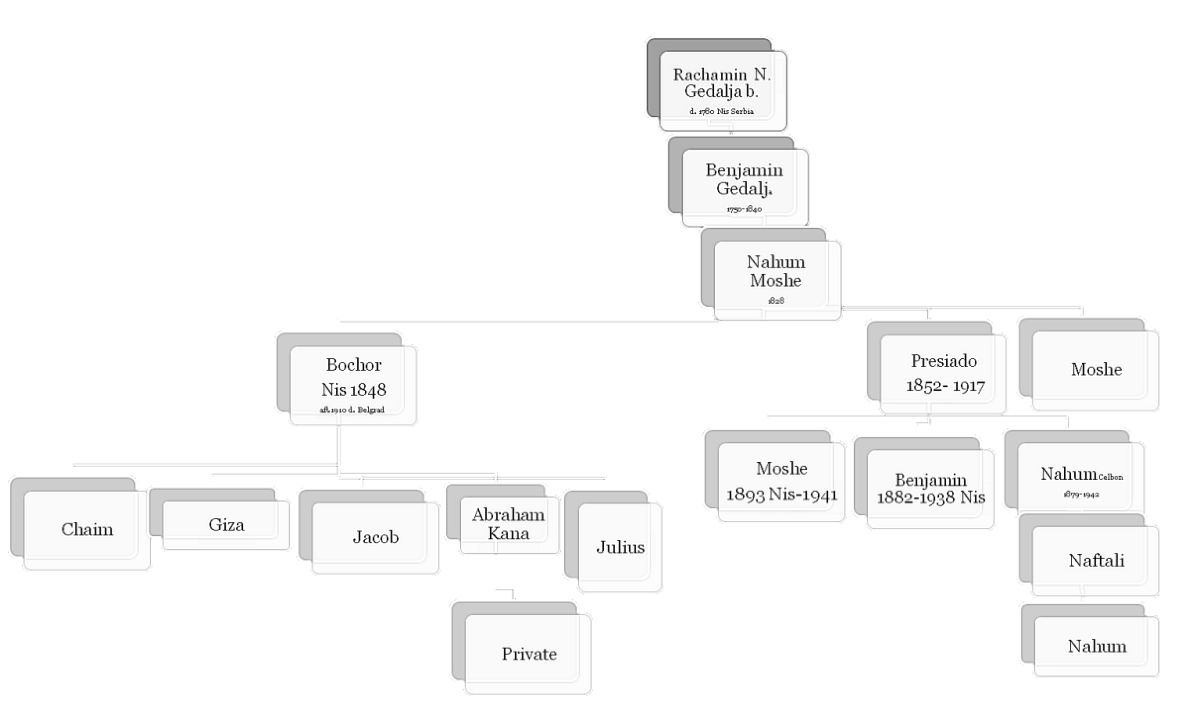

Figure 1 shows why I believe that Rabbi Rachmim Gedalia probably was my husband’s fourth great-grandfather. I am not sure if the rabbi’s second name was Naftaly or Nehemiah, but both names appear on my husband’s family tree over the years. Nehemiah and Nahum (my husband’s name) have the same Hebrew meaning: both names derive from the Hebrew word “Nechama” which means consolation or condolence. My husband’s name is Nahum and so was his grandfather’s name, while his fourth great-grandfather was Nehemiah, but also Rahamim, which means mercy.

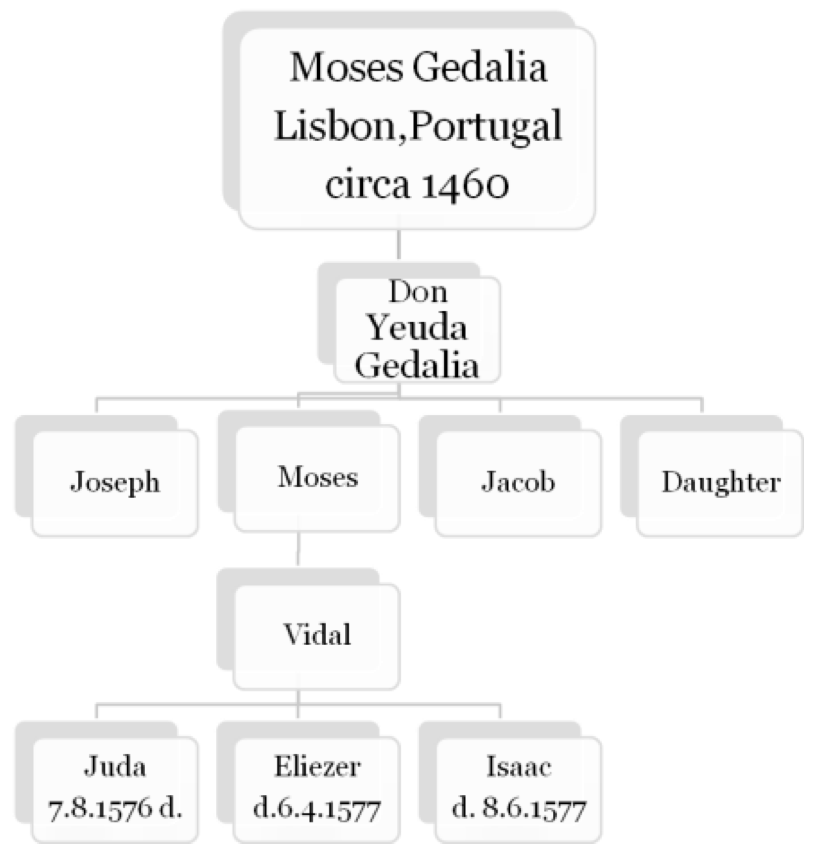

Going back to the books, I started with the Portuguese Jewish community and Toledano’s Hebrew Printing House14 where Don Yeuda Gedalia was an associate. He arrived in Salonika in 1505 with sons and an uncle, the famous sage Nissan Bibash. Numerous books mention Don Yeuda Gedalia, especially those by Emmanuel, Friedberg, Rosanes and Yaari.15

Figure 2 is a small family tree I constructed for Don Yeuda Gedalia from the above-mentioned sources. Oneof Don Yeuda’s sons, Moses, author of Masoret Hatalmud Bavli (Heritage of the Babylonian Talmud) moved to Livorno, Italy.Some family members died during earthquakes and plagues in Salonika, and we see below the inscriptions on their tombstones in Molcho’s book.16 Many others left and were scattered throughout the Ottoman Empire and beyond.

I have found Gedalias from Salonika in Yad Vashem Pages of Testimony, but have not traced them to their ancestors. The earliest I have found by birth date are Joseph Gedalia, born in 1840 and his wife, Dulca. Rivka Gedalia, born in 1865, married Daniel Russo, son of Nissim and Bienvenida, born in 1880, father of Aaron. From the names, it is clear that on the eve of World War II, Salonika was still a Sephardic Jewish community.17

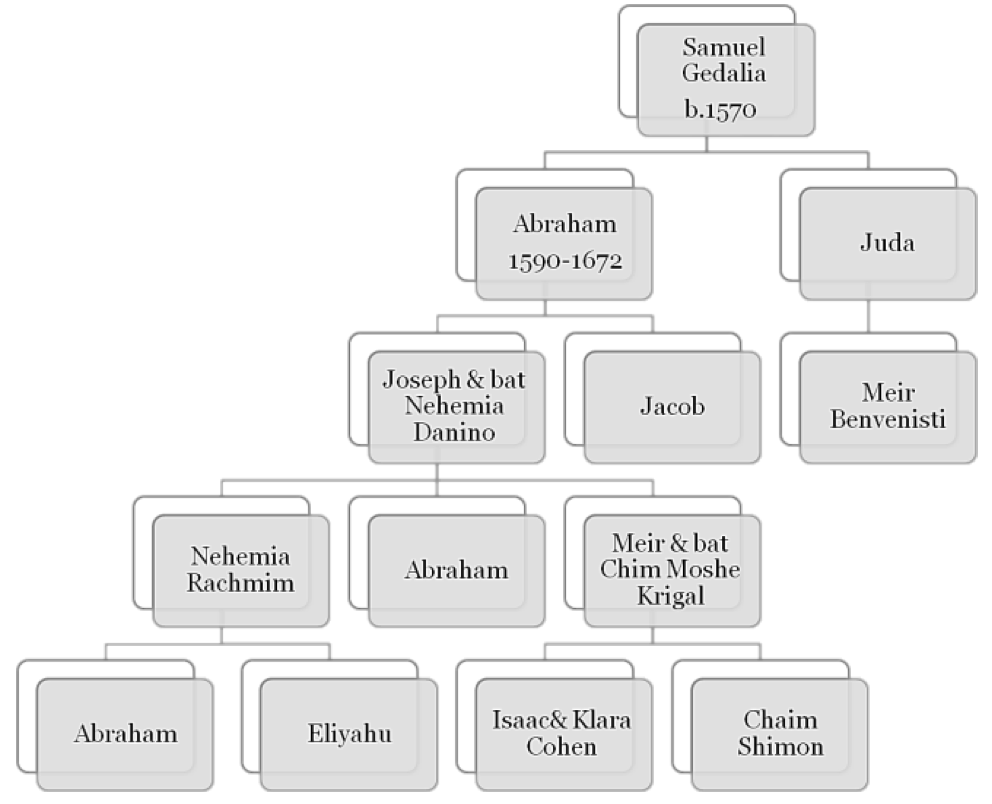

A branch of Gedalias from Salonika arrived in Eretz Israel at the beginning of the 16th century.18 I was able to build the tree represented in Figure 3 again from the books mentioned below. Abraham, son of Samuel, no. 2 in the chart, is mentioned as a descendant of Don Yeuda. He wrote a renowned commentary on Yalkut Hashimoni and published it in Italy where he also was serving as an emissary from the Jerusalem Sephardic community between 1648 and 1660. Abraham was known to be a disciple of the false Messiah, Shabbetai Zvi.19 Some tombstones in the Nis cemetery have symbols believed to have been of those Shabbetaim (followers of Shabbetai Zvi).

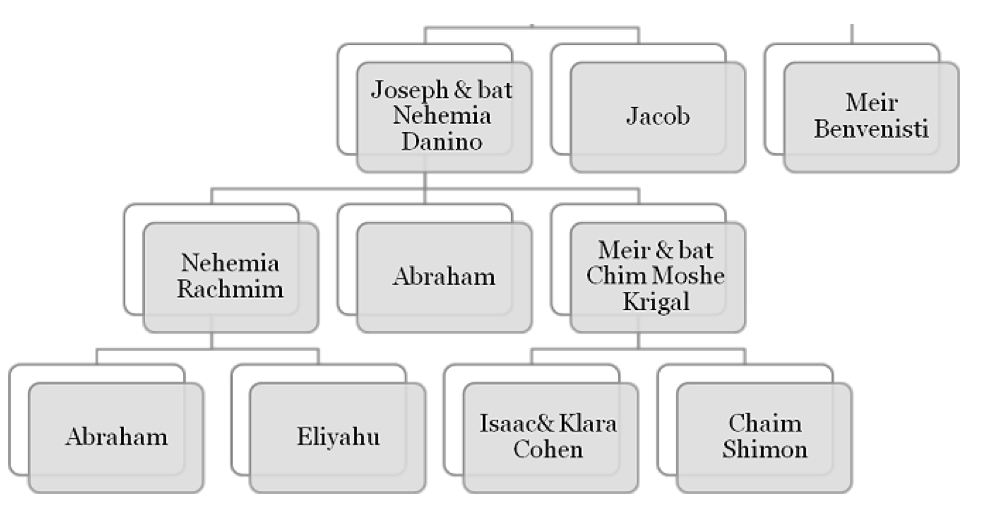

Joseph, son of Abraham, no. 3 in Figure 4 was Hebron’s emissary to Egypt in 1704 and was killed enroute to that country. He is mentioned in Molcho’s book20 about the Salonika interments, right beside Don Yeuda’s grandchildren. One may, therefore, take it for granted that the Eretz Israel branch, indeed, was related to the Salonika branch.

Meir, no. 7 and Chaim Shimon, no. 8 on the chart were emissaries to North Africa. Isaac, no. 9 was an emissary to Togarma, Turkey, and returned to Hebron in 1765. Eliyahu, no. 10 on the chart, was an emissary to Tiktin, Lithuania, in 1785. I was most interested in Nehemia Rachamim, no. 5 on the chart, because he had the same name as the Nis rabbi.Nonetheless, I needed to complete my research on all the other branches of the Gedalias before I could come to a conclusion about from where Rabbi Rachamim Nehemia had been summoned to Nis.

I was thrilled when I found Romanelli’s21 book, Masa B’arav (Travel in the Arab World)22in thebasement of the Israeli National Library, as he introduced me to two additional branches of Gedalias.The Guedalias of Mogador, Morocco, were a rich and famous family of merchants. They were called Ma-a-ravi-im (westerners) and Ild El Cazan (sons of the rabbi). According to Romanelli, their given names (Jacob and Yeuda ) were bestowed in honor of two brothers who were their ancestors who used to live in Amsterdam.

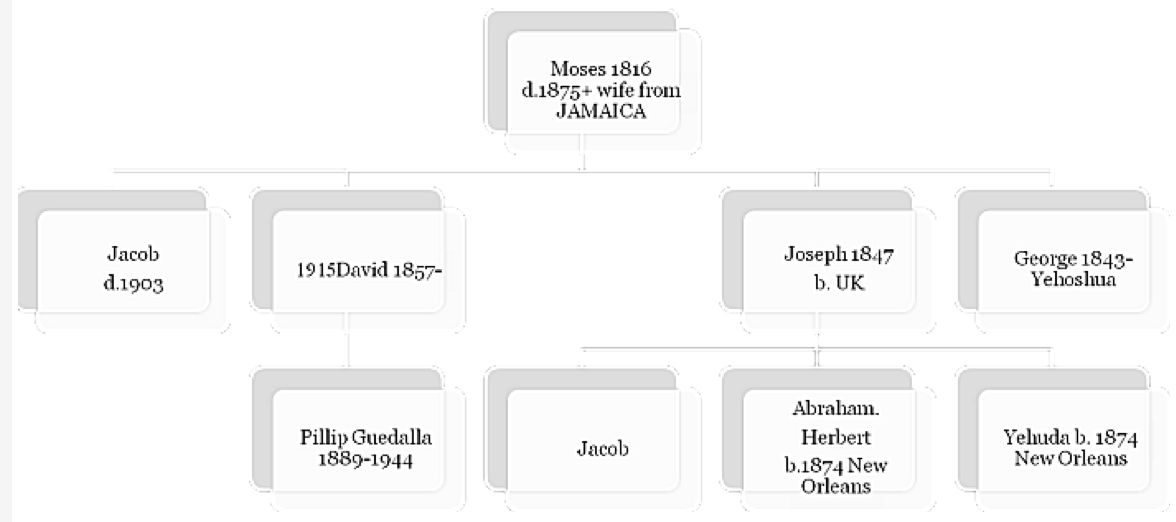

Some members of the Mogador family moved to Gibraltar while others relocated to London. Among the members of the London family was the prominent Yeuda—no. 2 on the London Geudalia family tree in Figure 5—who came from Mogador in 1873 and married Esther Montefiore and who built a large Sephardic yeshiva in Jerusalem. His son, Chaim, married Yemima Montefiore. Another son, Moses (no.10 on the London chart), was the grandfather of Philip Guedalla (1889–1944), a well-known British barrister, popular historical travel writer and biographer.

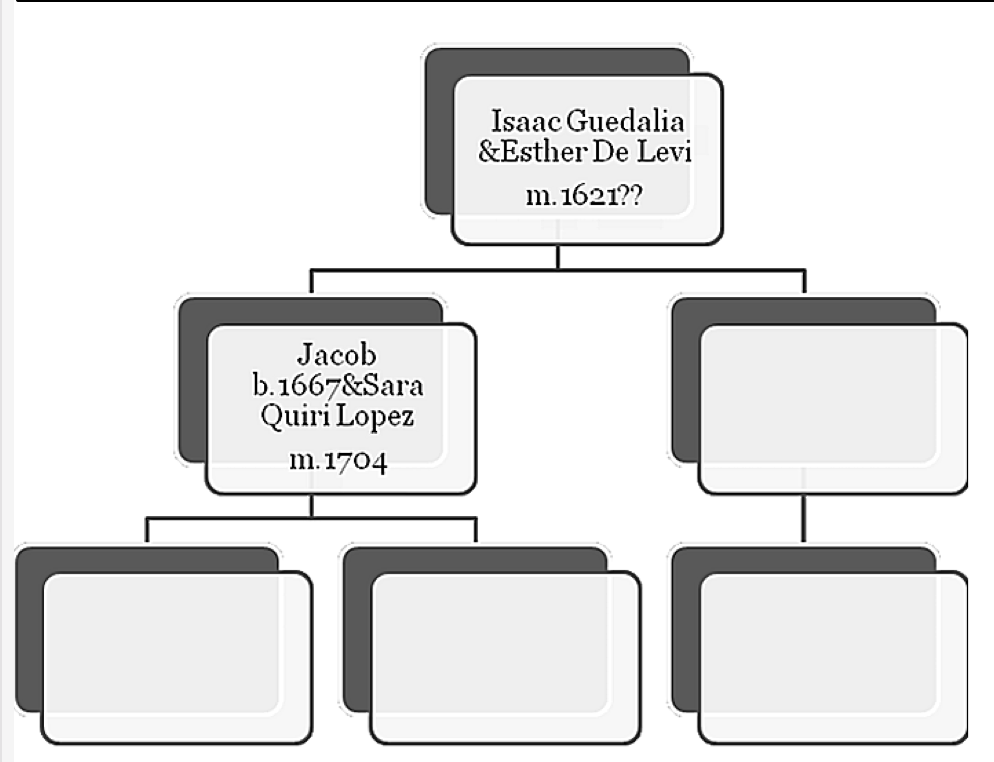

Wanting to trace the forefathers of the Mogador family back to Amsterdam, I examined the marriage indexes of the Amsterdam Sephardic community23 and created four branches, which I still cannot connect at this time. I did, however, find men named Jacob, one of whom was the ancestor of Jacob from Mogador.Figure 6 is the Amsterdam Gedalia family chart.

Since Romanelli mentioned immigration from Morocco to Gibraltar, I also followed that branch of the Guedalia family and discovered that their roots were in Livorno, Italy. Aaron Guedalia was born in Livorno circa 1760, as was his son, Jacob. Whether or not they were descendants of our Salonika Moses (son of Don Yeuda) is still an open question.

Eventually, the huge Guedalia family left Gibraltar. Moses immigrated to the United States in 1865 and founded a Portuguese synagogue in New York. His sons, Jacob and Hiram, moved to the Sephardic communities in New Orleans and Georgia. Leon left for Amsterdam and, after a few years, followed family members to the United States.

Another branch I have been tracing is the Guedalias from Jamaica recorded in the book The Jews of Jamaica Tombstones. This was a small branch headed by Samuel Guedalia who was born in Amsterdam in 1728 and arrived in Montego Bay, Jamaica, in 1756. His daughter, Hanna, married a Corinaldi of an Italian Sephardic family, and his son Moses (1775–1858) immigrated to the United States.24

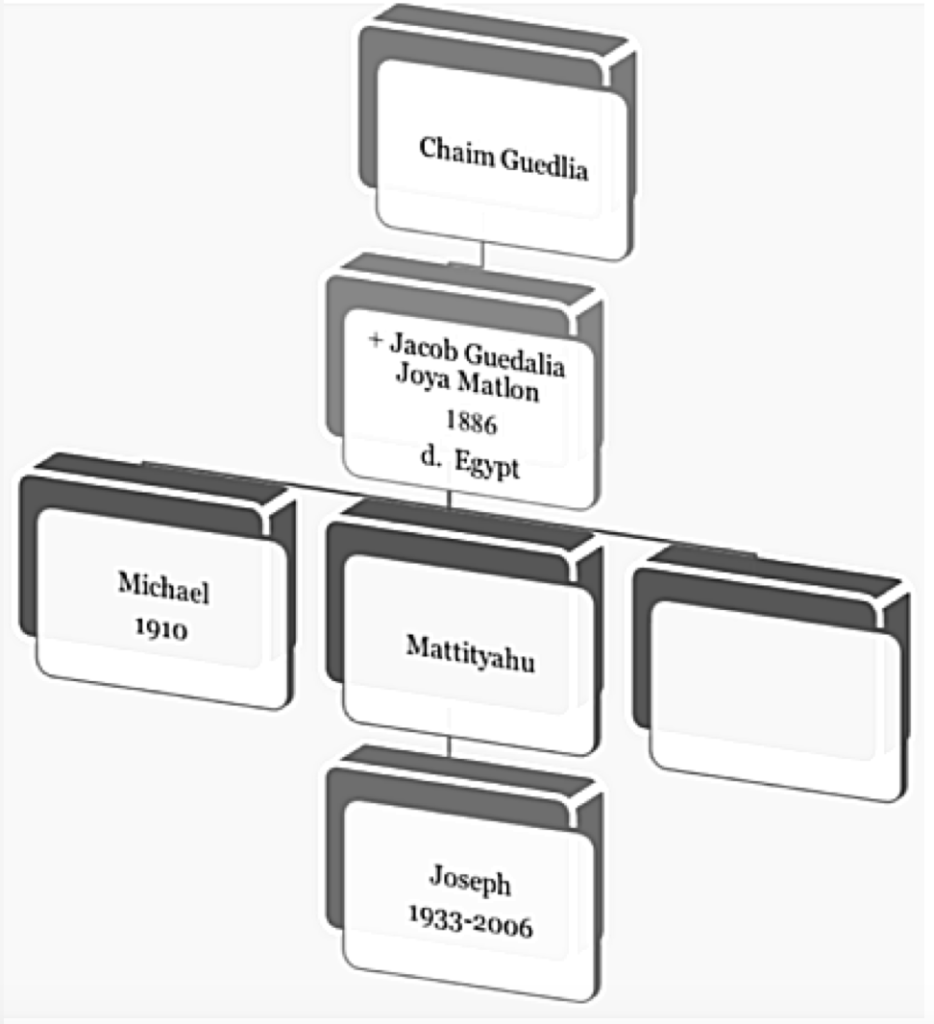

My final Geudalia branch is from Livorno. Livorno was an earlier home of two Geudalia branches that I have found with roots in Egypt.25 See their chart in Figure 7. The Y-DNA of one member of this branch, Amir Guedalia, an Israeli whom I came to know quite well, does not match my husband’s DNA results. This demonstrates that probably not all the Gedalias are members of one unique clan.

Conclusions

After having consulted numerous books, articles and archival records, I believe that I am able to point to the origins of my husband’s family in Nis, Serbia. Mapping all of the major branches of the Sephardic Gedalias and Guedalias reveals only one that has our family’s given names—Nehemia and Nahum. I believe that Rabbi Rachamim Nehemia/Naftaly Gedalia was summoned in 1786 to Nis from Eretz Israel, and that he was a grandson of the Hebron chief rabbi either by his son Abraham or his son Eliyahu. Neither of his sons appears in the Montefiore census for 1839.26

Support for my hypothesis comes also from researchers who believe that the Nis cemetery has Shabbetaim signs on its tombstones.27 We know that Nehemia’s grandfather, Abraham28 (1590–1672), was a disciple of Shabbetai Zvi. If indeed a branch of the Gedalia family went from Eretz Israel to Nis, this might account for the cemetery symbols.

Notes

1. Nafaly Bata Gedalja, a Serb officer in captivity in Nuremberg, Germany, five years and thus survived.

2. Costa, Isaac da, Bertram Brewster and Cecil Roth, “Notable Families Among Sephardic Jews” Oxford University Press, H. Milford, 1936

3. Olsen, V. “Aliases in,” ETSI, vol. 4, 2001

4. The Babylonians destroyed the Holy Temple in Jerusalem and exiled many Jews in 3338 (423 BCE); they appointed Gedaliah ben Achikam as governor of the remaining Jews in the Holy Land. In memory of Gedaliah’s tragic death and its disastrous aftermath, we fast every year on the 3rd of Tishrei, the day after Rosh Hashanah.

5. Loker, Z. (ed.) Toldot Yehudei Yugoslavia. The Yugoslav Association Tel Aviv,1971. (The History of the Jews of Yugoslavia)

6. Lebl., Z, Do Konaconog Resenja Jevreji u Seriji, Beograd, 2002.

7. Loker, Z. (Ed.) Pinkas Hakehilit Yugoslavia, Yad Vashem, Jerusalem, 1988. Pages 196–200 (Encyclopedia of Jewish Communities Yugoslavia)

8. Loker, Ibid page 198

9. According to Loker, Ibid p. 200 only one surviver returned to Nis

10. Jasmina Ciric is the president of Nis Jewish Community and editor of http:// elhttp:// elmondosefard.wikidot.commondosefard.wikidot.com

11. Don Yeuda Gedalia arrived from Lisbon where he was a member of the staff at Toledano’s Printing house. Many arrived with this immigration wave including the Ibn Yaya brothers. Perhaps they were not expelled but certainly driven out.

12. This is a most common belief among Sephardic researchers because, unlike Ashkenazi families, Sephardic had their names very early, some even believe that it was as early as the Babylonian exile. Since this was an early stage in my research, I believed so too.

13. Gedalia can also be an Ashkenazi surname most prominent is that of the chief rabbi in Copenhagen, Denmark, in the 18th century.

14. See Eliezer Toledano, scholar who went from Toledo to Lisbon, http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/loc/Lisbon.html and https://blogs.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/mullerlibrary/category/hebrew- printing/incunabula/https://blogs.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/mullerlibrary/category/hebrew- printing/incunabula/

15. Emmanuel, S.I. (The Sages of Salonika) Gedolei Shaloniki l’dorotam, Tel Aviv, 1935. Freidberg, C.D. (History of the Hebrew printing in Italy, Spain. Portugal, Turkey and more) Toldot Hadfus Haivri b’medinot italia, Ispamia, Portugal, Togarma and more, Antwrepen, 1934,

Rosanes, S. (The History of the Jews in Togarma based on first hand documents) Divrei Yemei Israel b’Togarma Al Pi Mekorot Rishonim, Tel Aviv, 1929

Yaari, A. (Emissaries from Eretz Israel) Shluchei Eretz Israel, Jerusalem, 1976

16. Molcho, S. (At the Salonika Cemetery) B’bait Ha’almin shel Yehudei Shalonika Tel Aviv, 1932

17. Kounio, H. The Jews of Thessaloniki, 2010

18. Gaon, M.D. (The Eastern Jews in Eretz Israel) Yehudei Hamizrach b’Erertz Israel, Jerusalem 1937 and Barnai,J. (These are the names of Jerusalem citizens 1760–1763) V’ele shmot Yehudei Yerushalayim in Catedra ,72 ,June 1996, pp. 135–168

19. Shabbetai Zvi ,1626–1676 was an ordained rabbi of Romaniote origin and an active kabbalist throughout the Ottoman Empire who claimed to be the Jewish Messiah. In 1666 upon his arrival in Constantinople, he was imprisoned and chose to convert to Islam rather than face death.

20. See footnote 14.

21. Romanelli Samuel Aaron 1757–1817, Italian Hebrew poet and traveler, Arrived in Morocco in 1787.

22. Romanelli, S.A. (Travel in Arab World) Massa ba- Arav, Berlin, 1792; repr. with intro

23. http://www.dutchjewry.org/phpr/amsterdam/tim_sephard_ marriages/menu.php. Also http://dutchjewry.org/phpr/amsterdam/ port_isr_gem_burials/amsterdam_port_isr_gem_burials_list.php. Also HTTP://familysearch.org/wiki/en/The_Knowles_Collection:_

Jews_of_Europe

24. Barnett, R. and P. Wright “The Jews of Jamacia: Tombstone Inscription 1663–1880” Jerusalem, Ben Zvi Ins.

25. One family, that of Amir Geudalia, knew of her Livornese roots as his grandfather received Italian citizenship in Cairo. I believe they might have been descendants of the son of Don Yehuda (the printer) who moved to Livorno from Salonika.

26. www.montefiorecensuses.org

27. Many older gravestones bear mysterious carvings linked to Jewish mysticism—half-spheres arranged in various patterns; geometric forms; snakes and other symbols that some believe are linked to followers of the 17th-century false messiah Shabbetai Zvi.

28. Toldot Gedolei Israel www.hebrewbooks.org/pagefeed/ hebrewbooks_org_44042_94.pdf