The first time I visited the half-Dutch, half-French island of St. Martin/St. Maarten in 1991, I heard that it once had a Jewish community. St. Maarten is a 36-square-mile island in the eastern Caribbean, located between St. Thomas and St. Eustatius where the Dutch and French sides of the island share a “no-passport-needed” border.

[This article was first published in the Summer 2017 edition of AVOTAYNU, The International Review of Jewish Genealogy, and is based upon a presentation at the Orlando IAJGS conference in July 2017. To obtain a subscription to AVOTAYNU, please visit https://www.avotaynu.com/journal.htm – Ed.]

It was my good fortune to meet my beloved under a moonlit sky in St. Maarten in 1993 and would, henceforth, call that island my home. I met the small local Jewish community that began in the 1960s and again was told there once had been a Jewish community on the island—but when and where? That was unclear. All I heard and was shown were crumbling remains of what was said to have been the synagogue and vague references to the location of the Jews’ burial ground. Where were the marble tombstones that gave witness to the past? How did the community disappear without a trace and who were they? How did we lose this piece of our Caribbean Jewish connection and history? I undertook to find some answers.

The research was like peeling an onion—one layer at a time, one source at a time, trying to piece together a lost history. A chance meeting with the island’s notary resulted in a coveted invitation to look at his files. (The island now has three notarial offices.) A notary represents both sides in a real estate transaction. The original notary’s office houses in a fireproof safe hand-written copies of land transactions going back to the early 1800s. Most deeds are handwritten in Dutch on old parchment paper and nearly impossible to read; they required translation that took several years.

“Nothing remained of them, not even the memory,” said Baruch Spinoza in the 17th century, referring to the Jews of Spain and Portugal, but he could have been talking about the Jews of St. Maarten.

Expulsion from Spain and Portugal

The expulsion of the Jews from Spain, and later from Portugal, started in August 1492, which coincided with Columbus’s first voyage to the New World. Subsequently, more than 300,000 Jews left the Iberian Peninsula for communities around the Mediterranean. Jews settled in the Balkans, England, France, Germany, Holland, Italy, France, North Africa, and Turkey. Some other Jews sailed to the New World and found islands and havens with freedom for Jews unknown in Europe.

Brazil Connection

The Dutch controlled the northeastern part of Brazil from 1625 to 1654. During that period, two thriving Sephardic communities, one in Amsterdam, the other in Recife (known as Mauristaad), Brazil, led the world in finance, insurance, shipping, slave trading, and sugar. Judaism in the New World traces its roots to the cataclysmic exodus of the Jewish community of Recife, Brazil, in 1654 when the Portuguese defeated the Dutch and regained control of the northeastern province of Brazil.

Many Brazilian Jews returned to Amsterdam. Other Jews settled in freedom-loving Surinam. Many others went to Curacao, making it a major Jewish center and the spiritual leader for America’s first synagogues. Some Jews settled on British Barbados and still, others went to the short-lived Jewish community on Martinique. Jews settled in Nevis and perfected the process of crystalizing sugar; many found fortune in pirate-loving Port Royal, Jamaica. A famed 23 managed to make it to New Amsterdam, which became New York City.

In the 1700s, the communities of St. Eustatius, St. Maarten, St. Thomas and St. Croix were established creating a network of related New Christians and Jews with different surnames. Two brothers with different names made it impossible to trace family trees, and many changed their names to Christian names.

St. Eustatius – St. Maarten Connection

From the early 1700s, the Dutch encouraged Jews to settle on the Caribbean island of St. Eustatius. They knew that a Jewish presence guaranteed a lively merchant community and trade, thereby bringing wealth to the motherland. By the start of the American Revolution, St. Eustatius was a mixed Ashkenazic and Sephardic community of more than 100 families on an 8.1 square mile island; these elements often were at odds with one another.

At the start of the American Revolution, French King Louis XVI and Spanish King Charles III, who were cousins, formed the trading company Roderique Hortalez et Cie. This company was responsible for the purchase and stockpiling of weapons, gunpowder, and muskets. The munitions were shipped to the island of St. Eustatius and from there to the American colonies where they were the primary source of weapons and material for General Washington and his fledging American troops.

In 1781, British Admiral George Rodney attacked St. Eustatius with a heavy force and, after occupation, separated the more than 100 Jewish heads of household, stripped them of their wealth and expelled 30 to the island of St. Kitts. Most of the rest of the community relocated to Danish St. Thomas. In the 1790s, the community reached 151 under the leadership of Cantor Jacob de Robles, but the European wars fought on Caribbean waters led to the demise of business on St. Eustatius and by 1826, the last Jewish widow had died. After 1826, no Jews remained on St. Eustatius.

A small reference in Isaac Edgar and Suzanne A. Samuel’s book The History of the Jews of the Netherlands Antilles, (1970) spurred on my investigation of St. Maarten. Samuel noted that two years after Rodney’s attack on the St. Eustatius’ Jewish community, the St. Martin synagogue had grown to the point of needing a more permanent home. On November 6, 1783, the leaders of the Jewish community of St. Martin (known as the Machmad) sought permission from the board of the Spanish Portuguese Synagogue in Amsterdam to approach the West India Company for authorization to form a congregation and draw up bylaws. The Amsterdam parnassim (synagogue administrators) delegated their secretary, Daniel Jesurun Lobo, to discuss the matter with the attorney for the company. The congregation of St. Martin asked for more prayer books and a Torah. The tradition was that the Spanish Portuguese Synagogue would give new congregations a Torah with a red cover. (A colleague found a reference in Portuguese from the Spanish Portuguese Synagogue in Amsterdam’s reference library and shared it with me, actual proof of the request.)

Search for the Synagogue

At my behest, my husband’s cousin, who worked at the St. Martin land record office, received permission in 2010 for me to view its archival records. On the notarial deeds in the land transfer record, I found a bombshell. Written in the flawless script were the words “Jewish Synagogue,” evidence that in 1783 St. Martin had a large enough Jewish population to form a congregation and build a synagogue.

Other records showed that, in 1879, a property was sold for $150 Spanish dollars. The notarial reference for its northern boundary was “two lots formally the Jewish Synagogue.” Sixteen years later, in 1895, the property changed hands again and the boundary in the north was described as “the land called the Jewish Synagogue” with a measurement of 10 meters and 20 centimeters (equal to 33.4 feet). The property sold again in 1910, but the reference to the Jewish Synagogue was not used. It had disappeared.

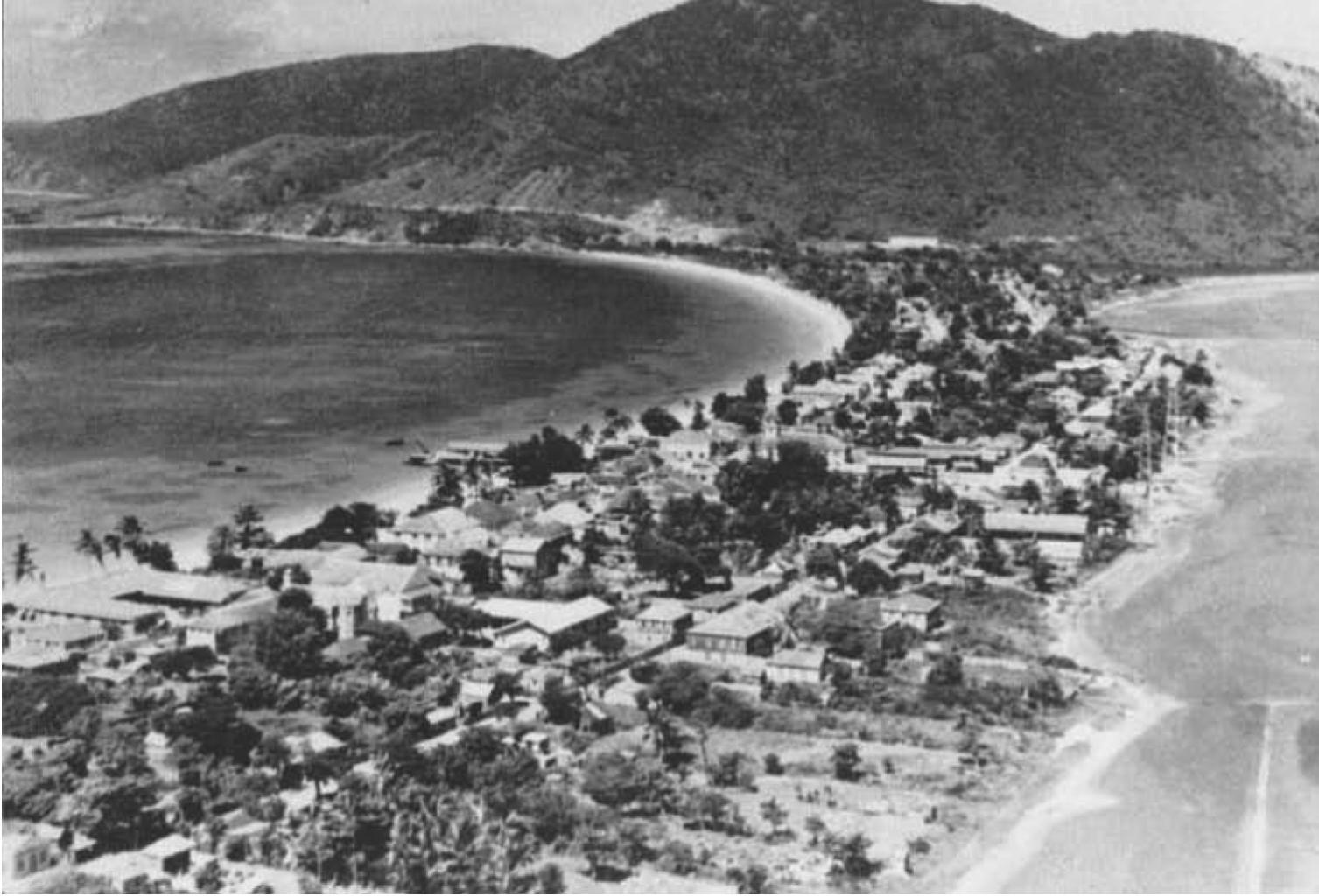

Many older residents on the island who shared recollections of conversation with their grandparents and Johan Hartog’s History of St. Eustatius and St. Maarten, confirmed that the synagogue stood on the property of the former West Indian Tavern (today, Guavaberry). The property has the oldest ruin in the town of Philipsburg.

St. Maarten’s Early Jewish History

The first recorded Jew to settle on St. Maarten was Jacob Gomez who came from Curacao in 1735. He was followed by a Mrs. Silva, a widow who moved to the island with her son and daughter about 1740. During a legal proceeding in the 1740s, Gomez insisted on swearing on the Five Books of Moses. Records also show a Jacob Dias Delgado who lived in St. Maarten in 1778.

“Economic conditions between 1733 and 1783 showed a constant upward tendency under Philips and Heyliger, and among the many whites who settled on the island during that time were Jews.” (Hartog, J, History of Sint Maarten/St. Martin, 1981)

Other records document the lively and sometimes heated correspondence between the Pereiras, David Israel and his two sons Isaac and Moses, with the board of the Spanish Portuguese Synagogue in Amsterdam in the 1790s. The Pereiras had been active in Honen Dolim in St. Eustatius and David had been a St. Eustatius Machmad, a board member of the Israel synagogue.

Jacob Gomez de Mesquista is listed in the island census of April 5, 1791, along with his four male slaves, the legal limit for non-agricultural households. The birth of Samuel Sasso is recorded in 1805. (Branches of the Sasso family still live in Jamaica and St. Thomas.) The archives also recorded the death in 1820 of Moses German of the “Portuguese rite,” (which means that he was Jewish) who was buried in the Jewish burial ground.

What Happened to the Synagogue

Records from the land office, census, the personal files of former Lieutenant Governor Mathias Voges, scores of interviews and the notary office helped peel another layer off the onion.

The St. Maarten Synagogue likely was built of wood with the eastern wall made of ballast stone, stones carried as ballast on ships arriving with very small cargo loads. A massive hurricane hit the island in 1819, leaving little standing. “Of the former existence of a synagogue at the east end of the Achterstraat (Front Street) to the part of the south, there remains nothing more than a heap of ruins covered with noxious weeds,” according to Marten Douwes Teenstra, a bookkeeper who visited the island in 1828 to study efficiency among the sugar plantations. His letter proved that there was once a synagogue—and Jewish life and life cycle events.

Continued Jewish Life

Notarial records of land sales and wills demonstrated the existence of Jewish life on the island from the 1820s through to the 1850s. A will appeared in the file pertaining to the property on which the synagogue was located. What originally was thought to be a misfiling turned out to be the key to understanding how the synagogue property ended up with five different owners. It showed that the Jews who were on the island after the synagogue was destroyed in 1819 still had a semblance of a community. Each person owned a portion of the synagogue and eventually sold or willed their portions.

Samuel Henriques of Curacao moved to St. Maarten, married and fathered four children. He died on September 25, 1854, and was buried in the Jewish burial ground on St. Maarten. He owned two-tenths of a share of the property where the synagogue had stood. Moses Phillips, a well-known St. Maarten landowner in the 1830s and 1840s, owned a 2/5 share of the property on which the synagogue had been located. In his will, Philips designated two executors, one of whom was Judah Cappe, a Jew of St. Eustatius who lived in St. Thomas. He also freed his slaves and left a legacy to the Jewish yeshiva in Dessau, Germany.

Last Jews on St. Maarten

Without a physical synagogue since 1819, faced with the abolition of slavery on the French side in 1848 and Dutch side by 1863, the Napoleonic Wars, and the diminishing plantation system, the Jews left St. Maarten. Holland and the Dominican Republic had entered into a commercial treaty and some families may have sent their sons to the Dominican Republic. Most of the St. Eustatius community went to St. Thomas which is where their menorah is now. Panama was the bright star of the future; many likely moved there. Of course, the United States always beckoned. By the time slavery was abolished in 1863, St. Martin likely had no remaining Jewish residents.

Search for the Jewish Burial Ground

“In Jewish religious community life—to a greater degree than elsewhere – the establishment of common consecrated burial ground is a significant sign of permanent settlement.” Rabbi David de Sola Pool, Portraits Etched in Stone (1952).

Knowing that the establishment of common holy burial ground is a sign of a community and with irrefutable notarial proof of the existence of a Jewish synagogue, I wanted to confirm the presence of a Jewish burial ground. That proved to be both easy and difficult. Folklore indicated that the old burial ground was underneath what is today the former Radio Shack building in Philipsburg. More than 50 local references, coupled with Dr. Hartog’s History of Sint Maarten-St. Martin made it clear that there had been a burial ground, e.g., “Up to this day, as we heard ourselves in 1977, a path along the former Jewish cemetery is still called in popular language ‘Jewish Cemetery Alley’.” (Hartog, 1981)

The first notarial proof of the existence of the Jewish Burial Ground on St. Maarten was recorded on January 6, 1855, in a deed that referenced its northern boundary as the “Jew’s Burying Ground.” When the property changed hands in 1920, that notarial deed referenced the northern boundary as the Jewish Burial Ground measuring 140 feet long, an indication of the southern boundary as well as the size of the cemetery.

In a deed without notarial boundaries dated May 1929, the Lieutenant Governor of St. Maarten acted as the seller on behalf of the government and sold the Jewish burial ground to the Caines family, who owned it until 1980. An obscure law dating back to 1867 (501/85 references Article 173) allowed the Governor jurisdiction to waive the ownership of government lands. A piece of the land was sold in 1948, and the family who built on the property found human bones.

At that time, there was no one to speak up for the Jewish community, and we do not know if anyone in Curacao, the administrator of the island, was aware of the sale and the ramifications for the future. The Cannegieter family purchased the property in the early 1980s and built a mixed commercial and residential building. At that location, they started the first electronics store under the Radio Shack franchise and the building became known as the Radio Shack Building. Radio Shack closed in 2015. All the deeds (nine in total) for the surrounding land show that the properties either were sold or given by the government. All reference it as lands that were part of the former Voormalige Joodse Bergraaftplaats (Jewish burial ground).

With the permission of the owners, Barbara and Diedrick Cannegieter and Dr. Jay Haversier, the government archaeologist of the Netherlands Antilles, I organized an archaeological dig behind the Radio Shack building in August 2010. The site had been totally built upon with only a narrow alley between two buildings. A trench of 6 feet by no more than 20 inches was dug. That was all the room there was, and the land was soft from heavy rainfall.

The results were stunning. On the second day of the dig a skull was found at a depth of 120 centimeters.

Who Was He?

Having watched enough CSI, NCIS and Law and Order television shows, I knew that I needed expert help at that point. Accordingly, I contacted Catyana Skory Falsetti of the Crime Lab of the Broward Sheriff Office, Fort Lauderdale, Florida. Falsetti is a forensic artist who has spearheaded a national campaign to give identities to unknown bodies. She agreed to give the man a face and the Broward County Sheriff’s Office donated her services At that time, this was one of the few U.S. police departments with a full-time forensic artiSt. Skory, whose fortitude and talent over three years to give the skull a face was amazing. She used state-of-the-art facial reconstruction techniques and consultations with Dr. Albert Dabbah, a world-renowned plastic surgeon in Boca Raton, Florida, for tissue markers. Mark Kemper, President and CEO of Engineering and Manufacturing Services donated his company’s services, scanned the clay facial reconstruction and printed out a 3D model. Because it is illegal to transport human remains over international borders, a copy of the skull was made and my husband hand carried it back to Florida.

Forensic DNA was submitted for testing to Dr. Chris Craig of William and Mary College, Williamsburg, Virginia. Dr. Tony Falsetti, a former University of Florida forensic anthropologist came to the island and viewed the original skull. He determined that the remains were those of a man about 48 years old when he died, most likely of a tooth abscess. DNA confirmed that the man was Jewish. He belonged to haplotype group U of the Sephardic Jewish ancestral group with ties to St. Eustatius and Barbados.

Copying of the evidence and recreation of the face of the unknown Jew of St. Maarten attracted the attention of the American Academy of Forensic Sciences. “The 19th Century Jewish Cemetery in St. Maarten – Historic Facial Approximations Using Modern Technologies – Doorway for Forensic Cases” was presented by Catyana Skory Falsetti in Washington, DC, on February 22, 2013, at the American Academy of Forensics annual meeting. It was a landmark because copied evidence was used in a case of identification and facial reconstruction when human remains could not be moved over international borders except by a law enforcement professional.

Jewish St. Maarten Today

In 2012, the local community erected a plaque denoting the Jewish burial ground of St. Maarten with permission of the property owners, Barbara and Diedrick Cannegieter, and the sponsorship of Diamonds International, a large retail jewelry company. The St. Maarten Museum has an exhibit with an information panel and the original bust done by Catyana Skory of the Broward Sheriff’s office along with a copy of the skull.

St. Martin/St. Maarten has an active Jewish community today. Jews from Curacao moved to the island in the 1960s and established businesses. As the island’s tourism grew, a small local community developed that is joined by visitors. In 2010, a Chabad House was established to service the Jewish communities and visitors on both the Dutch and French sides of the island.