Ashkenazi Jews (from the Hebrew word for “German”) are the largest of the Jewish groups and number some 10 to 11 million people today in a worldwide Jewish population of 13 million people (Reviewed in Ostrer, 2001; Ostrer, 2012). During the first millennium of the Common Era, the Jewish progenitors moved north across the Alps, probably from Italy. By the ninth century, the early Ashkenazi Jews settled in the cities of the Rhineland—Worms, Mainz, Speyer, and others.

[This article was first published in the Summer 2017 edition of AVOTAYNU, The International Review of Jewish Genealogy, and is based upon a presentation at the Orlando IAJGS conference in July 2017. To obtain a subscription to AVOTAYNU, please visit https://www.avotaynu.com/journal.htm – Ed.]

Large-scale Jewish migration into Poland started during the 13th century. (Weinryb, 1973). In time, their communities spread to other countries of Eastern and Central Europe. Subsequently, the population grew, so that it numbered five million by the start of the 20th century. Extermination by Nazis and Soviets during the Second World War led to the loss of six million Jews, mostly Ashkenazim. Migrations in the late 19th and early 20th centuries led to the formation of large Ashkenazi Jewish communities in the United States, Canada, England, Australia, South Africa, Argentina, and Israel.

To supplement knowledge from the historical record from the late 19th century onward, population scientists, many of them Jewish, attempted to understand the origins of Ashkenazi Jews and their relatedness to other Jewish and non-Jewish groups. Both physical measurements and subsequent analysis of heritable markers (blood groups, serum proteins, histocompatibility groups and, more recently, variation in DNA) were used. The analytical methods reflected the ones commonly used in population genetics at the time that these studies were published. Now they include analysis of genetic markers based on variation in DNA, such as single nucleotide variants (A or C at one site, G or C at another site), or longer DNA segments, called haplotypes or identical by descent segments (marked by A at site one and G at site two, C at site 3 and so forth). The identification of millions of genetic markers has improved the accuracy of analysis compared to earlier times because no single marker gets undue weight.

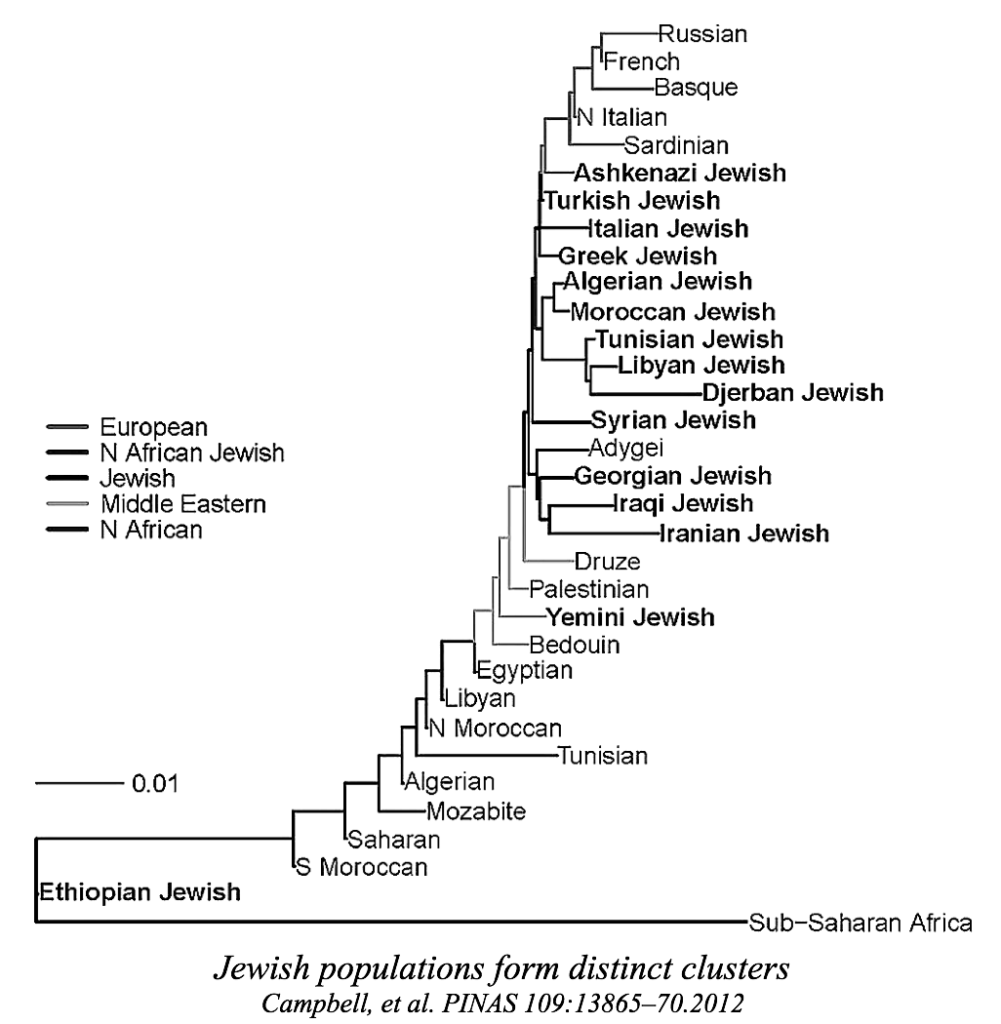

Based on sharing large numbers of genetic markers, the methods test whether members of an individual group are more closely related to each other than they are to members of other groups; thus, they test whether members of a group form their own genetic cluster. The methods then test the relatedness of one group to another and produce metrics, such as genetic distances, or graphics, such as nearest neighbor-joining trees. These metrics and graphics demonstrate hierarchies of relatedness for people from different population groups. Additional methods explore the contributions of ancestral populations that led to the formation of contemporary groups. All of these methods have been applied to many of the world’s populations. Researchers can confirm or refute each other’s findings by analyzing different datasets for the same populations. Researchers can apply new methods of analysis and/or add data from new groups for comparison by reanalyzing existing datasets. Such approaches have been used in recent times to study Jewish origins and relatedness.

In 2010, two research groups, one led by Karl Skorecki and the other led by me, published studies about the origins of Ashkenazi Jews and other Jewish groups in the journals, Nature and the American Journal of Human Genetics, within one week (Atzmon, et al., 2010; Behar, et al., 2010). Although Karl and I are personal friends and have sometimes collaborated on research projects, these studies were performed and published independently without prior consultation. The studies had similar observations and conclusions: Jewish populations originated in the Middle East and shared ancestry with one another. The major Jewish groups are European, North African and Middle Eastern Jews (Campbell, et al., 2013). European Jews (Ashkenazi, Italian, Sephardic) are derived almost equally from Southern European and Middle Eastern populations, reflecting conversion and intermarriage during Classical Antiquity. Despite the large geographical range that they assumed over time, subgroups could not be identified within the Ashkenazi Jewish population.

This work has been expanded by Itsik Pe’er and his collaborators, including me, to show that based on the analysis of the DNA segments shared among Ashkenazi Jews, the number of founders for this population may have been as few as 350 and that the founding event occurred about 1,000 years ago (Palamara, et al., 2012; Carmi, et al., 2015). More recent work from this group of collaborators has shown that ~85% of the European segments of the Ashkenazi Jewish genome came from Southern Europeans with the remainder coming from others (Xue, et al., 2017). All of this work precludes that the Khazars, a Turkic people whose kingdom flourished in Southern Russia between ~750 and 965 CE, were the progenitor population of Ashkenazi Jews, but does not exclude that their descendants were contributors to the Ashkenazi Jewish population. But Khazars may have not been contributors at all. In a history monograph, Shaul Stampfer questioned the accuracy of the sources that are cited as evidence of the Khazars’ conversion, suggesting that it might better be viewed as a myth (Stampfer, 2013).

Against this backdrop, Eran Elhaik published a reanalysis of data from the Skorecki study arguing for a major Khazarian origin for Ashkenazi Jews. He based his observation of their relatedness to contemporary Armenians and Georgians, groups from the Caucasus that he suggested could serve as proxies for the Khazars (Elhaik, 2013). His study was criticized for sampling only a small number of Ashkenazi Jews, for assuming that Armenians and Georgians would be proxies for Khazars, and for accepting the Khazarian hypothesis as fact.

Arguing that Northern Caucasus populations might represent a better proxy for Khazars, Doron Behar, Noah Rosenberg, and their collaborators compared a larger sample of Ashkenazi and other Jews to 15 Caucasus populations as well as European and Middle Eastern populations (Behar, et al., 2013). Their study found no particular similarity between Ashkenazi Jews and Caucasian populations.

Subsequently, Elhaik published a follow-up study in which he applied his technique of geographic population structure (GPS) (Das, et al., 2016). This method assumes that genetic coordinates can be overlaid with geographic coordinates. In fact, this method has worked quite well when applied to the populations of Europe. By Elhaik’s reckoning, the ancestral Ashkenazi Jewish population mapped to the southern coast of the Black Sea in northeastern Turkey. He even identified four villages in the regions with names similar to Ashkenaz.

Elhaik also partnered with the linguist, Paul Wexler, to argue that the Yiddish language was Slavic, rather than Germanic in origin. This led to a rather elaborate hypothesis that Jewish merchants from this region converted and admixed with the Slavs, and subsequently Khazars, to create contemporary Ashkenazi Jews.

A team of investigators led by Pavel Flegontov and Alexei Kassian pointed out that Elhaik misapplied the GPS technique because it is intended for inferring a geographic region where a modern, unadmixed population is likely to have arisen. It is not suitable for admixed populations nor for tracing ancestry that occurred 1,000 years ago (Flegontov, et al., 2016). Simplistically stated, if the Ashkenazi Jews are presumed to have dual Middle Eastern and Southern European origins, then the GPS method would infer their origins to be at some midpoint, such as the Black Sea coast of Turkey. The Flegontov and Kassian group also demurred on the issue of a Slavic origin for Yiddish.

Population genetic studies support dual Middle Eastern and Southern European origins for Ashkenazi Jews, their distinct founding event and their relatedness to other Jewish groups (Ostrer and Skorekci, 2013). Some issues of Ashkenazi Jewish population genetics remain. The observed relatedness of Ashkenazi Jews to Georgian Jews and to the Central Asian Adygei people is unexplained. It is possible that Ashkenazi Jews contributed to the formation of these groups. The contemporary view of Ashkenazi Jewish origins appears to be quite durable based on many analyses of large numbers of individuals by independent investigational groups.

Literature Sources

Atzmon, G., L. Hao, I. Pe’er, C. Velez, A. Pearlman, P. F. Palamara, B. Morrow, E. Friedman, C. Oddoux, E. Burns and H. Ostrer (2010). “Abraham’s children in the genome era: major Jewish diaspora populations comprise distinct genetic clusters with shared Middle Eastern Ancestry.” Am J Hum Genet 86(6): 850–859.

Behar, D. M., M. Metspalu, Y. Baran, N. M. Kopelman, B. Yunusbayev, A. Gladstein, S. Tzur, H. Sahakyan, A. Bahmanimehr, L. Yepiskoposyan, K. Tambets, E. K. Khusnutdinova, A. Kushniarevich, O. Balanovsky, E. Balanovsky, L. Kovacevic, D. Marjanovic, E. Mihailov, A. Kouvatsi, C. Triantaphyllidis, R. J. King, O. Semino, A. Torroni, M. F. Hammer, E. Metspalu, K. Skorecki, S. Rosset, E. Halperin, R. Villems and N. A. Rosenberg (2013). “No evidence from genome-wide data of a Khazar origin for the Ashkenazi Jews.” Hum Biol 85(6): 859–900.

Behar, D. M., B. Yunusbayev, M. Metspalu, E. Metspalu, S. Rosset, J. Parik, S. Rootsi, G. Chaubey, I. Kutuev, G. Yudkovsky, E. K. Khusnutdinova, O. Balanovsky, O. Semino, L. Pereira, D. Comas, D. Gurwitz, B. Bonne-Tamir, T. Parfitt, M. F. Hammer, K. Skorecki and R. Villems (2010). “The genome-wide structure of the Jewish people.” Nature 466(7303): 238–242.

Campbell, C. L., P. F. Palamara, M. Dubrovsky, L. R.

Botigue, M. Fellous, G. Atzmon, C. Oddoux, A. Pearlman, L. Hao, B. M. Henn, E. Burns, C. D. Bustamante, D. Comas, E. Friedman, I. Pe’er and H. Ostrer (2012). North African Jewish and non-Jewish populations form distinctive, orthogonal clusters. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109(34): 13865–13870.

Carmi S, Hui KY, Kochav E, Liu X, Xue J, Grady F, Guha S, Upadhyay K, Ben-Avraham D, Mukherjee S, Bowen BM, Thomas T, Vijai J, Cruts M, Froyen G, Lambrechts D, Plaisance S, Van Broeckhoven C, Van Damme P, Van Marck H, Barzilai N, Darvasi A, Offit K, Bressman S, Ozelius LJ, Peter I, Cho JH, Ostrer H, Atzmon G, Clark LN, Lencz T, Pe’er I. (2012) Sequencing an Ashkenazi reference panel supports population-targeted personal genomics and illuminates Jewish and European origins. Nat Commun. 5:4835. doi: 10.1038/ ncomms5835.

Das, R., P. Wexler, M. Pirooznia and E. Elhaik (2016). “Localizing Ashkenazic Jews to Primeval Villages in the Ancient Iranian Lands of Ashkenaz.” Genome Biol Evol 8(4): 1132–1149.

Elhaik, E. (2013). “The missing link of Jewish European ancestry: contrasting the Rhineland and the Khazarian hypotheses.” Genome Biol Evol 5(1): 61–74.

Flegontov, P., A. Kassian, M. G. Thomas, V. Fedchenko, P. Changmai and G. Starostin (2016). “Pitfalls of the Geographic Population Structure (GPS) Approach Applied to Human Genetic History: A Case Study of Ashkenazi Jews.” Genome Biol Evol 8(7): 2259–2265.

Ostrer, H. (2001). “A genetic profile of contemporary Jewish populations.” Nat Rev Genet 2(11): 891–898.

Ostrer, H. (2012). Legacy: a Genetic History of the Jewish People. New York, Oxford University Press.

Ostrer, H. and K. Skorecki (2013). “The population genetics of the Jewish people.” Hum Genet 132(2): 119–127.

Palamara, P. F., T. Lencz, A. Darvasi and I. Pe’er (2012). “Length distributions of identity by descent reveal fine-scale demographic history.” Am J Hum Genet 91(5): 809–822.

Stampfer, S. “Did the Khazars Convert to Judaism?” Jewish Social Studies: History, Culture, Society n.s. 19, no. 3 (Spring/Summer 2013): 1–72

Weinryb, B. (1973) A History of the Jews in Poland, (Jewish Publication Society of America, Philadelphia).

Xue, J., T. Lencz, A. Darvasi, I. Pe’er and S. Carmi (2017). “The time and place of European admixture in Ashkenazi Jewish history.” PLoS Genet 13(4): e1006644.