The Mediterranean is the name of the sea that lies “in the middle of the lands,” these lands being the continents of Africa, Europe, and Asia. The Italian peninsula is located centrally on this sea. Because of its strategic position, Italy served Jews as a crossroads between north and south, east and west, the Middle East and Europe. The Tuscany region, located centrally in this natural path, played a special role in Jewish history.

[This article was first published in the Summer 2016 edition of AVOTAYNU, The International Review of Jewish Genealogy. To obtain a subscription to AVOTAYNU, please visit https://www.avotaynu.com/journal.htm – Ed.]

The oldest Jewish writings from Israel to Europe involve Tuscany and genealogy. Sefer Yuhasin (the book of genealogies) is a family chronicle from the 8th and 9th centuries that describes the arrival of wise men (rabbis) from the Talmudic schools of the Middle East to Apulia, in southern Italy. These rabbis with their first-hand Talmudic knowledge brought directly from the areas where the Talmud was compiled, opened schools in Italy.

The sages and their descendants moved up to Rome and Tuscany, and from Tuscany, further north to Ashkenaz (Germany). The main center of this Dark Ages Judaism was the town of Lucca, Italy. Abraham ibn Ezra, who was born in Spain, lived in Lucca for several years about 1150, and the town was a leg of the travels of Benjamin of Tudela in 1165. Eleazar of Worms, a German rabbi of the 13th century, reports the arrival of sages from Babylon, their settlement in Tuscany and then, after generations of wandering from place to place, their arrival in the Rhineland.

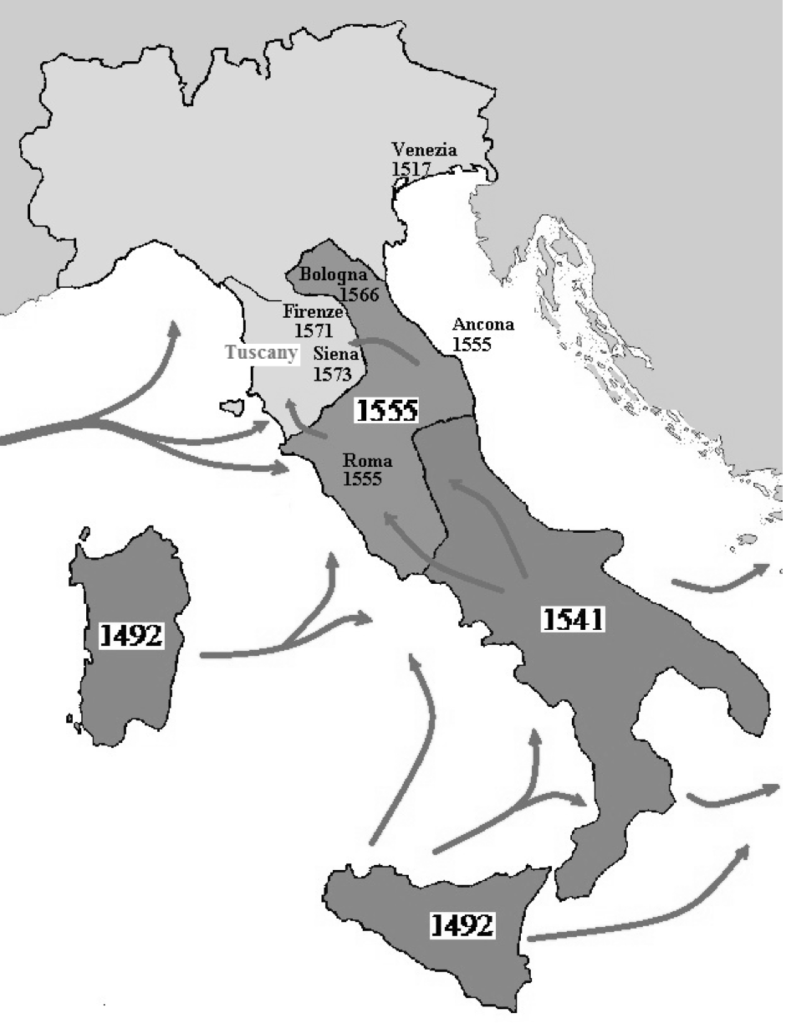

Map showing years of migration of Jews to Italy

At this time, the Italian peninsula was divided into tens of small states and Tuscany had fragmented into a dozen communal political powers. While increasing its wealth through business and mercantile activities, the city of Firenze(Florence)conquered a large part of the Tuscan region—Arezzo, in 1384; Pisa, in 1406; Siena, in 1555; Grosseto, in 1557; and Lucca much later, in 1847.

During the 14th and 15th centuries, the increasing influence of towns and decreasing influence of the Church gave rise to a flourishing of culture and arts, a period of passage between the Middle Ages and the Modern era called Rinascimento (Renaissance). The Jews were very active in the Renaissance, especially in Tuscany. They were physicians at the courts and cultural intermediaries—physicians, scientists, philosophers, traders, money lenders, and others—who, through networking, imported knowledge of magic, science and philosophy from the Arab countries and brought it to the Catholics and the Protestants of Europe. Above all, Jews were teachers of Hebrew to notable cultural figures.

The discovery of the Americas, the date that conventionally marks the beginning of the Modern Era, coincides with the beginning of a long period of expulsions of Jews from Spain and Sicily (1492), as well as persecutions and confinement in ghettos. In 1516, the first ghetto in the world was established in Venice. A few decades after the start of the Protestant Reformation in Germany, the Catholic Church began a Counter-Reformation, a return to orthodoxy. Because Italy had no Protestants, the Jews became the main target of the persecutions of the Catholic Church. These persecutions began with the burning of the Talmud (1553), then two bills in 1555 and 1569 that limited freedom for the Jews, established the ghettos and decreed the expulsion of the Jews from the entire Papal State, except for the cities of Rome and Ancona. This expulsion produced the flight of some Papal State Jews north to Tuscany.

In the 16th century, the policy of the Medicis, the family that ruled Tuscany, was ambiguous toward the Jews. On one hand, the Medicis needed to populate the coastal area of its dominions and especially the new port of Livorno (Leghorn), and for this, they invited Jews to settle there. On the other hand, the Medicis adopted the anti-Semitic policy of the Church and decided to establish ghettos.

Thus, the 16th century is the start of a dual history for the Jews of Tuscany. The proclamation of the Medicis that invited Jews to populate the coastal area mentioned explicitly, “To all of you merchants from the west and from the east, Spaniards, Portuguese, Greeks, Germans, Italians, Jews, Turks, Blacks, Armenians, Persians….” Jews arrived in large numbers. In two centuries, the Jewish population of Livorno increased many times, until it became half of the Jewish population of Tuscany and the second-largest Jewish community in Italy.

Jews in Livorno:

1642 1,100

1700 3,000

1738 3,500

1809 5,340

1880 4,000

In the interior of Tuscany, however, Jews were forced to live in ghettos. During the Renaissance, the Jews were very scattered throughout Tuscany and apart from a few major places—Firenze, Pisa, Prato, and Siena—most Jewish communities numbered just 20 to 30 people. In the years 1571 to 1573, however, the Medicis decided that the main towns of Tuscany, Firenze, and Siena, also should have ghettos and this is where the Jews were forced to live for the next two to three centuries. A third of Tuscany, the southern part called “Maremma,” bordered the Papal State. Maremma is where the “Jews of the Pope” came after their expulsion in 1569. The community of Pitigliano flourished here and the ghettos were established later.

In the 16th century, because of the expulsion from southern Italy and the segregation in the Papal State (1492–1555), Tuscany remained the Jews’ main Italian peninsula transit point. This period of reversals (capovolgimenti) for the Jews coincided broadly with the consolidation of their surnames. When the Jews lived in small communities spread around the country, the given name and the father’s name (“Gaio di Rubino”) were sufficient to identify the person. With the closures into ghettos, the migrations and urbanization, a surname became a necessary additional identification item. The adoption of surnames generally is the starting point for most genealogical research.

During their closure in the ghettos, the Jewish communities and the local communal authorities produced administrative documents that are good sources for genealogy. The first ghetto in Tuscany was built in 1570; others continued to be established until 1714. When the French army invaded Tuscany in 1796, the gates of the ghettos were opened and the Jews received full civil rights (1796–99).

The following dates must be noted when researching Tuscan genealogy: after the Congress of Vienna in 1815, the Tuscan rulers commanded a “restoration” of the political order and again Jews were ordered into ghettos; in 1860, Tuscany held a referendum for annexation to the Kingdom of Italy; and for a few years, 1865–70, Florence was the capital of Italy.

Genealogical Sources

Census of 1841. After the French Revolution and before the unification of Italy, in 1841, Tuscany took a census of its population. Before this census, all the surveys, catasti (cadasters), tassa del sale (salt tax), cittadinari (lists of citizens) and other fiscal documents were administered at the local level by various communal administrations. The 1841 census is the first census that covers all of Tuscany. The census records all family members by name, surname, age, profession, and capacity to read.

In the light of what we said above, at the moment of the census, the Tuscan Jewish population should have again been in ghettos. A thorough search of all the census registers, however, reveals a different picture. Surprisingly, Jews are spread throughout Tuscany. The census records 8,056 Jews, of whom 4,546 (56 percent) live in Livorno. Firenze has the next largest population with 2,273 (28 percent), followed by Siena with 369 (four percent), Pisa with 363 (four percent) and Pitigliano 360 (four percent). The remainder scattered among smaller communities. Apparently, after they had tasted freedom and equality of rights during French domination, some Jews refused to return to the old prohibitions and many did not return to the ghettos.

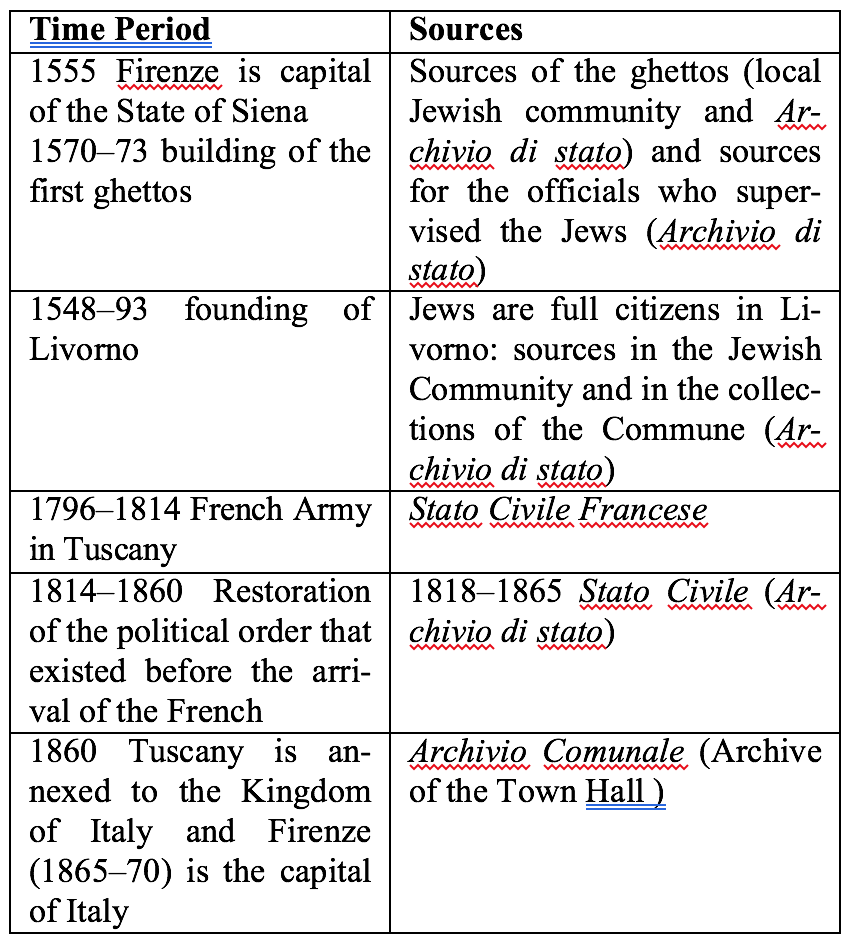

Beyond the 1841 census, sources for Jewish genealogical research in Tuscany vary from town to town. The table above indicates some sources for the major cities and towns, along with relevant corresponding history.