The Sousa Mendes Foundation actively seeks families who received lifesaving visas from the Portuguese diplomat Aristides de Sousa Mendes in the Spring of 1940. Sousa Mendes, stationed in Bordeaux, France, rescued thousands from the Holocaust by providing them visas to Portugal in violation of strict orders issued by his own government. For his courageous acts, he was subsequently put on trial in Portugal by the Salazar dictatorship and harshly punished. Sousa Mendes died in 1954, in poverty and official disgrace.

Decades after the war, his reputation was restored first by Yad Vashem, which in 1966 posthumously declared him a “Righteous Among the Nations,” and again during the 1980s by the Portuguese government, which formally apologized to his family and elevated him posthumously to the rank of Ambassador. The Sousa Mendes Foundation, established in 2010 as a partnership between the hero’s family and the families of some of those he rescued, is engaged in an unprecedented worldwide search for the visa recipients. These refugees came from all parts of Europe to the south of France (Bordeaux, Bayonne, Hendaye or Toulouse) during April, May or June of 1940, where they received Portuguese visas. The visas permitted travel via Spain to Portugal and ultimately to safe havens in the United States, Brazil, the U.K., and other points on the globe.

The Foundation is continually seeking to expand its knowledge of this important story. If you know of a family that escaped the Holocaust through Portugal between 1940 and 1942, please write to us at: info@sousamendesfoundation.org.

“Most people who were saved by Sousa Mendes don’t know that they were saved by anyone,” declared Dr. Sylvain Bromberger, professor emeritus at MIT and himself one of the lucky ones.

The rescue of these refugees had a significant effect on U.S. and world culture in literature, science, fashion, politics, and the arts. Notable Sousa Mendes visa recipients included Salvador Dalí, Hans and Margret Rey (authors of Curious George), the Imperial Habsburg family of Austria, members of the Rothschild family, and others. Most, however, were ordinary men, women, and children escaping the horrors of Nazi persecution.

To date, the Foundation has identified approximately 3,900 Sousa Mendes visa recipients individually by name. These refugees can be searched by country, by name, by the ships they boarded or by where they lived during their stay in Portugal. Each name is clickable to reveal the story behind the visa. Those for whom we have videos, photos, artifacts and testimonials are identified with the letters V, P, A and T, respectively. To access the database, please go here.

A Story of Moral Courage

[Ed. Note: The following is adapted from an article that originally appeared in PRISM — An Interdisciplinary Journal for Holocaust Educators published by Yeshiva University, Spring 2015, Volume 7, pages 72-78.]

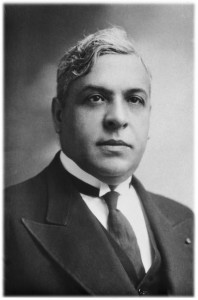

As the Portuguese Consul General stationed in Bordeaux, France, at the onset of World War II, 55-year-old Aristides de Sousa Mendes was confronted with the reality of thousands of desperate Jewish refugees seeking to escape the advancing German army.

Aristide de Sousa Mendes

As one refugee remembers,

We began to live visas day and night. When we were awake, we were obsessed by visas. We talked about them all the time. Exit visas. Transit visas. Entrance visas. Where could we go? During the day, we tried to get the proper documents, approvals, stamps. At night we tossed about and dreamed about long lines, officials, visas. Visas![1] (Gilbert, 2007, p. 126)

Portugal, though officially neutral, was under the dictatorial rule of António de Oliveira Salazar. Determined to keep refugees out for fear of attracting Hitler’s ire, Salazar issued a decree to all of his diplomats in November 1939 in a confidential memo called Circular 14. This document forbade the issuing of Portuguese visas to Jews expelled from their countries of origin, Russian citizens, holders of Nansen passports (those issued to stateless refugees), and other categories of Holocaust refugees, without prior approval from the Portuguese Foreign Ministry.

This order created a situation of moral crisis for Sousa Mendes, which intensified in June 1940 as Nazi troops were overrunning France. Should he fulfill his sworn duty to uphold the policy of his government, and leave the refugees to their fate? Or should he defy this direct order, issue the visas, rescue thousands of complete strangers at his own peril, and, in the process, throw away his 30-year career?

On a day now known as the Day of Conscience, Sousa Mendes decided to issue the visas.[2] He saved thousands of lives — some estimates place the figure as high as 30,000 — not only in Bordeaux, but also in the cities of Bayonne and Toulouse, where he gave orders to his vice-consuls to follow his example, and in Hendaye, where he handed out visas himself.[3] Yad Vashem historian Yehuda Bauer (2001) has described this unique operation as “perhaps the largest rescue action by a single individual during the Holocaust” (p. 249).

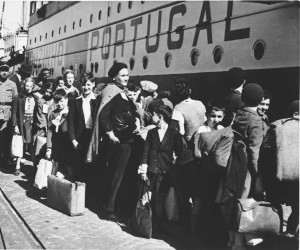

Sousa Mendes’s rescue operation resulted in a sudden and tremendous influx of refugees into Portugal in the spring and summer of 1940. “Lisbon was the bottleneck of Europe, the last open gate of a concentration camp extending over the greater part of the Continent’s surface” (p. 242), wrote Holocaust refugee Arthur Koestler in his 1941 memoir, Scum of the Earth. “By watching that interminable procession, one realized that the catalog of possible reasons for persecution under the New Order was much longer than even a specialist could imagine; in fact, it covered the entire alphabet, from A, for Austrian Monarchist, to Z, for Zionist Jew.” (p. 242)

Ironically, despite the Portuguese government’s official policy against accepting refugees, their presence in the country allowed the regime to take credit for their rescue, and the history books were written accordingly. “When Aristides de Sousa Mendes took it upon himself to save as many of the thousands fleeing the German advance in France as he could … he was challenging a political concept and confronting Lisbon with the creation of that most difficult of precedents, the humanitarian one,” explained Manuela Franco (2000), Director of the Diplomatic Institute at the Portuguese Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In her view, “the image of ‘Portugal, a safe haven’ was born then in Bordeaux, and it lasts to this day” (p. 19).

Sousa Mendes paid a heavy price for his civil disobedience. He was put on trial, found guilty, suspended from the diplomatic corps, and blacklisted. He was driven into poverty with no way to support his large family, which was socially shunned, and virtually all of his children were forced into exile. He died in 1954 in poverty and disgrace, almost erased from history. Only posthumously, beginning in 1966, was his act of moral courage recognized, not by his own country but by Israel, when he was awarded the title of Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem. Meanwhile, Salazar took credit in the postwar years for having let the refugees into his country. It was only following his death in 1970 and the Carnation Revolution of 1974 that Portugal began taking a sober look at the fascist elements of its wartime behavior, such as Circular 14. The whole Sousa Mendes story was unknown in Portugal until the 1980s, and only in 1999 did the Portuguese government finally redress its past mistreatment of its diplomat by offering reparations to his descendants.

Documenting Each Family: The Work of the Sousa Mendes Foundation

The Sousa Mendes Foundation, founded in 2010, seeks to document Sousa Mendes’s heroism.[4] Our research has as its ambitious goal to identify all Sousa Mendes visa recipients worldwide and trace each family’s story of survival. Beginning with scans from a handwritten visa registry book and cross-referencing it with ship manifests and other records, we have been able to reconstruct entire family groups, including names, faces, ages, artifacts, and testimonials, thus bringing each family’s story to life. A three-year grant from the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany greatly aided in this effort. Below, this essay describes the process we have used and highlights three individual cases.

Among the models for our project is Serge Klarsfeld’s (1994) magisterial book French Children of the Holocaust: A Memorial, a richly documented account of the more than 11,000 French children murdered in the Holocaust. While our project shares that undertaking’s goal “to fill in as many blanks as possible” (p. 104), the action we are documenting — rescue, not murder — is its mirror image. Accordingly, just as Klarsfeld uses deportation lists and camp arrival records to document the fate of the murdered Jews of France, so do we use ship manifests and immigration records to document the fate of those who were saved on French soil in the largest solo rescue operation of the war.

Sousa Mendes’s List

The issuing of visas at the Portuguese Consulate in Bordeaux took place in assembly-line fashion and involved the participation of Sousa Mendes; his secretary, José Seabra; two of Sousa Mendes’s sons; and two or three refugees. One person would collect the passport from the refugee, a second person would stamp it, Sousa Mendes would sign it, Seabra would assign the visa a number, and someone would record the date, visa number, and name in a ledger book.

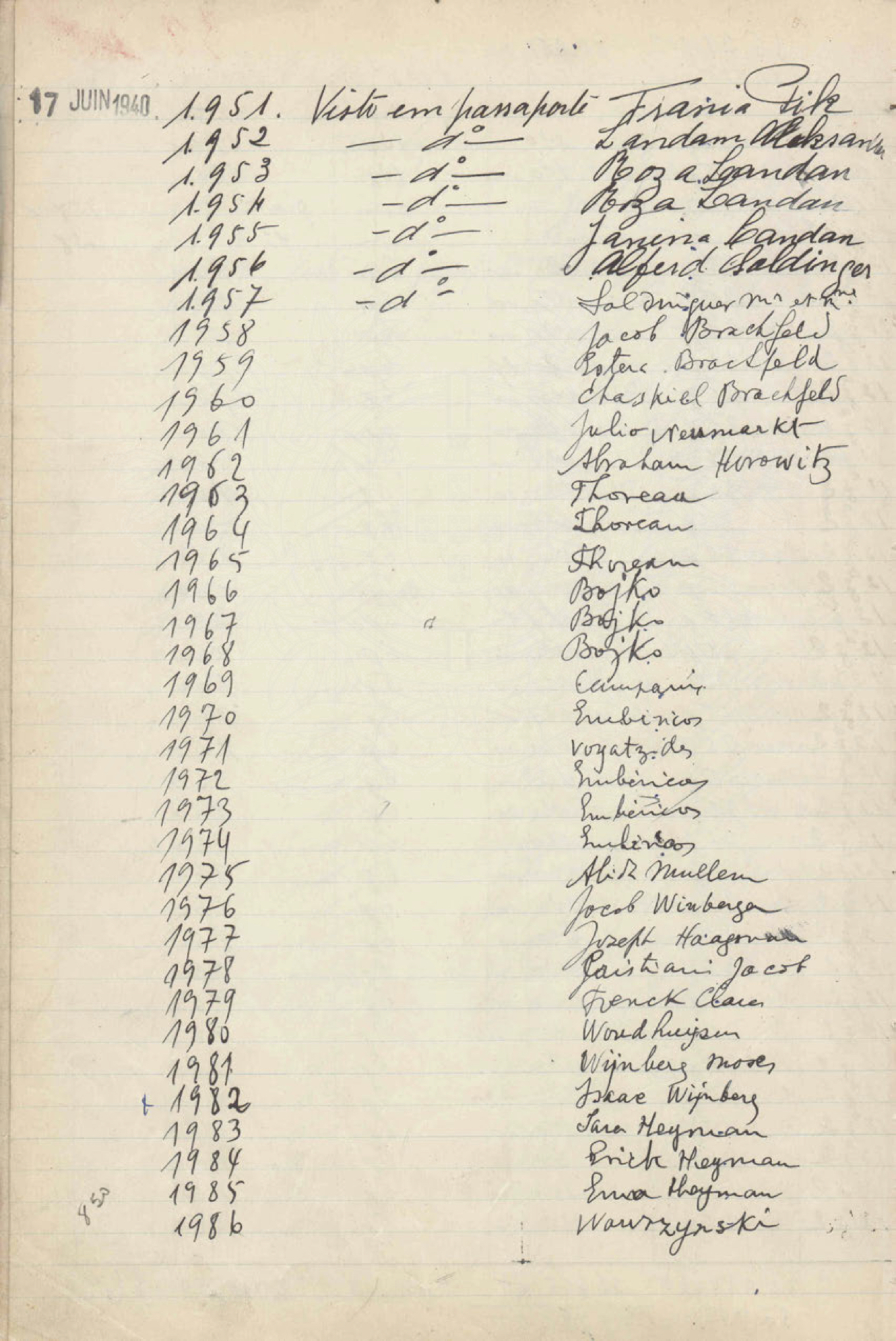

Like Schindler’s list, this is Sousa Mendes’s list. The book, dated 1939-40, was found when the Portuguese Consulate in Bordeaux was renovated years after the war, and is now housed in the archives of the Portuguese Foreign Ministry in Lisbon. It contains only about 2,000 names, as it lists only passport holders (i.e., adults) and does not include visas issued in the other cities under Sousa Mendes’s authority.

The research process involves several layers of work. First, we needed to decipher the names in the visa registry book, which were written in great haste, in a variety of hands and with frequent misspellings and abbreviations. We then grouped these names into families, cross-referenced, and verified them using ship manifests and online genealogical databases. This process allowed our team to ascertain each family group’s complete traveling party and add any missing names to our list. Thus we learned, for example, that in a family of two adults and four children, with only two visas granted, six lives were saved. We then culled further information from the manifests, including city of last residence. For any refugee families that had resided in Belgium, we obtained further information and documentation from the Foreigner Files in the Felix Archives in Antwerp, including photographs, dates and places of birth, alternate spellings of names, and maiden names.

The last stage in the process entailed (and continues to entail) identifying, locating, and contacting visa recipients or their descendants. This stage involves research into immigration records, obituaries, telephone directories, and social media. By the time we reach out to the families to ask for testimonials, photographs, passports, and other artifacts, we usually have a great deal of information to share with them.

Figures 1 through 11 below illustrate this process in action for three different families. (Click on any image to enlarge.)

Shown in Figure 1 is a page from Sousa Mendes’s list that lists visa nos. 1951-86, issued on June 17, 1940. The first step of the process consisted of ascertaining how many handwritings were present and deciphering their peculiarities. This page was clearly assembled in great haste; for example, for the first few lines in the middle column we see the abbreviation for ditto under the words visto em passaporte (visa in passport [of]), but soon this ditto indication is dropped. On this particular page, we see one handwriting (most likely that of José Seabra, Sousa Mendes’s secretary) on lines 1951-56 and one or possibly more handwritings (possibly of one of Sousa Mendes’s sons and/or a refugee volunteer) on 1957-86. Some visa recipients are clearly identified (e.g., visa no. 1958, Jacob Brachfeld, and no. 1962, Abraham Horowitz), whereas others are presented in abbreviated form (e.g., no. 1957, Soldinger Mr. et Mme, and nos. 1963-65, Thoreau/Thoreau/Thoreau. In some cases, the names are listed with the last name preceding the first (e.g., no. 1981, Wijnberg, Moses); in others, the last name is last (e.g., no. 1982, Isaac Wijnberg). In each case, the challenge is to establish the correct spelling of the name and then the identity of the individual (e.g., which Abraham Horowitz?). The haste with which the page was written is understandable when one realizes that it was assembled a mere three days after the fall of Paris, as the German army was approaching Bordeaux.

Spotlight: Heyman/Heymann Family

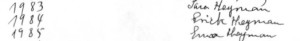

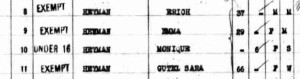

Figure 2 is a detail from Sousa Mendes’s list showing members of the Heyman family. Here we see visa nos. 1983-85, assigned to Sara Heyman, Erich Heyman, and Emma Heyman.

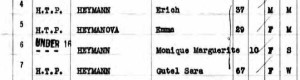

The same family appears in Figure 3, showing an excerpt of a ship passenger manifest for the September 1940 voyage of the Greek vessel Nea Hellas from Lisbon to New York.

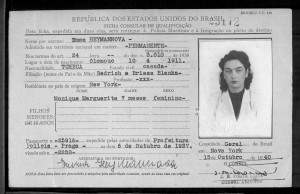

The manifest provides us with new information, including the full name of Sara Heyman (Gutel Sara Heyman) and the ages and relationships of the members of the family; she is the mother of Erich, who is married to Emma. We also learn that Gutel Sara is a widow (“W”). Most important, we learn of the existence of another family member: Monique Heyman, age six months, who was certainly on the passport of one of her parents. Thus we learn that with three visas from Sousa Mendes, four lives were spared, and we can add baby Monique to the list. Further passenger records on Ancestry.com reveal an alternate spelling of the family name — Heymann — as well as Americanized first names Eric, Emily, and Monica.

Searching for the name Monica Heymann in online marriage records, our research team member Marie J. Gomes was able to establish Monica’s married name, which led her to an entry Monica had contributed to her alumnae magazine in which she mentioned her children. This information led Marie to Monica’s daughter, Elisa, whom she contacted through social media. Elisa forwarded the inquiry to her mother, who sent us this reply:

I am totally surprised to find out that my family’s escape story is part of a bigger story. I am Monica David, daughter of Eric and Emily Heymann. I was born in February 1940 in France. I actually was born with the name of Monique Marguerite Heymann, which I understood to have been changed to Monica in the US. My father also brought his mother, Augusta Heymann, on that ship. Unfortunately, he was unable to convince my maternal grandparents to join us; they later perished in a concentration camp. We were not allowed immediate entry to the US, so we ended up in Brazil for some time (am not sure how long) and then were able to re-enter the US. (personal correspondence to Marie J. Gomes, May 14, 2012)

This testimony led us to Brazil immigration cards and to photos of the family members in 1940. Note that Emma’s name is given with the Czech feminine ending, as Heymannová. Baby Monique is listed, as well.

The Brazilian cards also list parents’ names, so they are a great source of maiden names of married female refugees. Here we see Emma’s parents listed as Bedrich e Briess Blanka, indicating that the maiden name would be Blanka — but is this record wrong? In fact, Blanka is a feminine first name in Czech, and Briess is more likely to be the surname. From Monica David’s testimony, we learned that Emma’s parents were Holocaust victims. A quick search of Yad Vashem’s Central Database of Shoah Victims’ Names yields a Page of Testimony for Blanka Briess, confirming that Briess is the correct surname. Gutel Heymann’s card provides her maiden name: Wolff. It further lists her nationality as German and indicates that her passport was issued in Berlin in 1939. On the basis of this information, we conclude that the middle name Sara was not her real name, but rather was the false middle name imposed by the Nazi regime on all Jewish women. We therefore strike it from her listing.

Finally, a search of passenger records for journeys from Rio de Janeiro to New York answers Monica David’s uncertainty as to how long the family was in Brazil, and naturalization records complete the story.

Here is the resulting entry for the Heymann family presented on our website: Heymann Family Page.

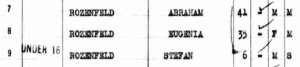

Spotlight: Rozenfeld Family

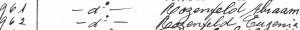

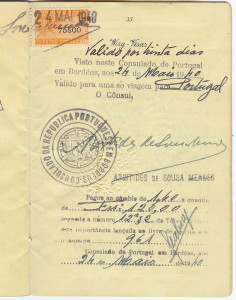

Next, we turn to the Rozenfeld family, whose visas were issued by Sousa Mendes in Bordeaux on May 24, 1940. Figure 6 shows the names of Abraham (misspelled Abraam) and Eugenia Rozenfeld as they appear in Sousa Mendes’s list as visa nos. 961 and 962.

Passenger records shown in Fig. 7 find them traveling on the Greek vessel Nea Hellas in July 1940 and reveal that they belong to a family of three: Abraham, 41; Eugenia, 35; and Stefan, 6.

A search on The White Pages identified a Stephen Rozenfeld of the right age and provided his address and telephone number. One of our team members, Sylvain Bromberger, called and confirmed that he had reached the right man. Rozenfeld, who had never heard of Aristides de Sousa Mendes, promptly located his parents’ World War II passports and kindly provided our team with scans and photographs.[5]

An exodus story emerged. Eugenia and Stefan Rozenfeld family left Poland in January 1940, shortly after the German invasion and just before the establishment of the Lodz Ghetto. They escaped to Belgium, where they were reunited with Abraham. On May 10, 1940, the Nazis invaded Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg. On that day, the family left Belgium, headed toward France, and reached Bordeaux, where they received the Sousa Mendes visas enabling them to enter neutral Portugal. From a 1940 letter written by Abraham Rozenfeld, we learned that they resided in Lisbon at that time. Here is the resulting page: Rozenfeld Family Page.

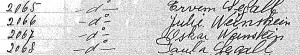

Spotlight: Segall/Weinstein Family

Finally, we turn to the Segall/Weinstein family, consisting of three generations: maternal grandparents Oskar and Julie Weinstein; parents Erwin and Paula Segall; and a child, Frederic Segall. The adults are enumerated in the visa registry book [Fig. 9].

The child’s name has been gleaned from ship manifests, as have the family members’ nationalities, places of birth, and places of last residence. Oskar and Julie are listed as Czech citizens residing in Nice. The passenger listings also include their daughter, Paula, and grandson, Frederic. Erwin, age 38, is missing from the manifest, and Paula’s marital status is given as “W” (widowed). His fate illustrates that being a refugee could itself become a death sentence for many.

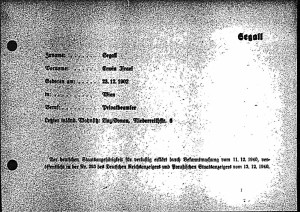

Why is Paula listed as stateless (nationality: “None”), along with her son, Frederic? A search for Erwin on www.ancestry.com yields the answer in a document issued by the Nazi regime [Fig. 11]

Note the middle name “Israel” imposed to all Jewish males by the Nazi regime. attesting that though born in Vienna, he had been stripped of his nationality by the Nuremburg Laws, as had been his Czech-born wife (who had become Austrian by marriage) and their child (also born in Vienna). Sousa Mendes, forbidden by Circular 14 from issuing Portuguese visas to stateless persons, nonetheless did so for the Segall family. Here is the resulting page on our website: Segall/Weinstein Family Page.

The three studies presented above are typical of the thousands of families that Sousa Mendes rescued from the clutches of the Nazi regime. The Heymann family story demonstrates the quirkiness of US immigration policy, which required many families to leave and then be readmitted. The Rozenfeld family is an example of double refugees: first from Poland, then from Belgium. The story of Erwin Segall, first stripped of his nationality and then dying during the exodus, illustrates the humiliation and danger of being a refugee. These stories serve as reminders that a life-saving visa by itself was not enough to ensure a successful exodus.

Adding Faces to Names

An important goal of our project is to put faces to as many names as possible. This is especially important in those cases where the refugee was unable to leave Nazi-occupied France despite the visa from Sousa Mendes, and was subsequently deported and murdered. We are aware of other cases where the refugees managed to embark on a ship, only to drown when the ship was torpedoed. We are able to obtain photos of the visa recipients from the Foreigner Files in the Felix Archives; Brazil immigration cards; and the families themselves, if we are in contact with them. The work done by our research team goes beyond a scholarly or educational function to serve a memorial role, as well.

The project has yielded numerous surprises. For example, we have identified a group of 152 Polish refugees who, by agreement between the Polish government-in-exile in London and the British government, transited through Portugal to Camp Gibraltar, a refugee internment camp barely mentioned in the scholarly literature, located on the British-owned island of Jamaica. We also have identified several hundred refugees who were aboard an American vessel, the SS Washington, that was nearly torpedoed by a German U-boat in June of 1940 upon leaving the port of Lisbon. We have been able to trace the migration via Portugal of German refugees to Brazil; Czech refugees to Mexico; Austrian refugees to Cuba; Dutch refugees to the East Indies; and Polish refugees to the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia. In one case, we were able to reunite families in Brazil and the United States who had escaped Europe together and kept photos of one another, but had not known of each other’s whereabouts since 1940. As the Holocaust was a shattering of the entirety of the Jewish people, we are gratified to be able to put a few of the shards back together.

In Portugal, under the leadership of architect Luisa Pacheco Marques and historian Margarida de Magalhães Ramalho, we worked with city officials in the border town of Vilar Formoso to create a permanent display on Aristides de Sousa Mendes and the visa recipients on the site of the very train station where most of the refugees entered Portuguese soil in 1940. The “Vilar Formoso, Frontier of Peace” museum opened in 2017. We further plan to work with the governments of France and Portugal to establish museum displays both in Bordeaux, where the events of 1940 transpired, and in Cabanas de Viriato the site of the Sousa Mendes family’s ancestral home. In North America we conduct educational events for all ages, such as exhibitions and film screenings, and have published a graphic novel aimed at a middle-school readership.

As survivor and author Roman Kent remarked in a speech at the Center for Jewish History (2011), the Allies won the war militarily, but it was the Righteous Among the Nations — those individuals in Nazi-occupied countries who at great personal risk refused to be bystanders in the face of evil — who won the war over morality, by safeguarding timeless humanistic values.[6] Similarly, in a July 2012 speech marking the anniversary of the Vel d’Hiv round-ups in Paris of 1942, French President François Hollande declared that in the dark days of World War II, when the collaborationist French government betrayed the trust of its citizens by failing to uphold their rights, it was the Righteous Among the Nations who saved France’s honor. Chief among these was Aristides de Sousa Mendes, whose rescue action on French soil was unparalleled.

Rescue list (partial)

The following list includes just a few of the thousands of individuals who received Portuguese visas from Aristides de Sousa Mendes:

Hamilton Fish Armstrong, founding editor, Foreign Affairs magazine

Eugene Bagger, journalist

Hélène de Beauvoir, painter, sister of Simone de Beauvoir

Dr. Daniel Branton, cell biologist

Dr. Sylvain Bromberger, philosopher

Salvador Dali, artist

Jean-Michel Frank, interior designer

Simone Gallimard, publisher

Colette Gaveau, pianist

Richard de Grab, photographer

Archduke Otto von Habsburg, nemesis of Hitler and heir to the Austrian throne

Robbert Hartog, Canadian business leader and philanthropist

Dr. Lissy Jarvik, professor of medicine

Maria Lani, actor and artist’s model for Matisse, Chagall and others

Robert Lebel, art critic

Kizette de Lempicka, daughter of the artist Tamara de Lempicka

Witold Malcuzynski, pianist

Dr. Daniel Mattis, physicist

Leon Moed, architect

Alfred Montesinos, former president of Cartier

Hans and Margret Rey, authors of the Curious George series

Paul Rosenberg, art dealer

Rachel Rosenthal, performance artist

Baron Maurice de Rothschild and the Rothschild family

Boris Smolar, chief European correspondent, Jewish Telegraphic Agency

Sonia Tomara, journalist

Tereska Torrès, French-Polish writer and one of the first women to fight for Charles de Gaulle

Julian Tuwim, Polish poet and nephew of the pianist Arthur Rubinstein

Jean-Claude van Itallie, actor, stage director and playwright

King Vidor, Hollywood film director

Albert de Vleeschauwer, a leading member of the Belgian government in exile

References

“American Writers Escape Into Spain.” (1940, June 26). The New York Times, p. 15.

Ávila, Miguel Valle (2013, October 1). “Was Lisbon Journalist “Onix” Portugal’s Deep Throat? Aristides de Sousa Mendes Defended in the US Press in 1946.” The Portuguese Tribune, p. 28.

Bauer, Yehuda (2001). A History of the Holocaust. Danbury, CT: Franklin Watts.

Franco, Manuela (2000). “Politics and Morals.” In Spared lives: The Actions of Three Portuguese Diplomats in World War II.

Gilbert, Martin (2007). Kristallnacht: Prelude to Destruction. New York, NY: Harper Collins.

Hollande, François (2012, August 18). The “Crime Committed in France, by France.” The New York Review of Books. Retrieved from http://www.nybooks.com/blogs/nyrblog/2012/aug/18/france-hollande-crime-vel-d-hiv/

Klarsfeld, Serge (1996). French Children of the Holocaust: A Memorial. New York: NYU Press.

Koestler, Arthur (2006). Scum of the Earth (1941). London: Eland.

Martins, Anibal (1967, October 13). Ainda o Caso do Consul Sousa Mendes [Letter to the editor]. Diário de Noticias (New Bedford, MA), p. 2.

“Spain Halts Flow of War Refugees; Border Guards Hold Up Most of Those Seeking Entrance” (1940, June 25). The New York Times, p. 3.

Spared Lives: The Actions of Three Portuguese Diplomats in World War II [exhibition catalog]. (2000). Lisbon: Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Notes

[1] Although not spoken by a Sousa Mendes visa recipient, these sentiments were widely shared by Holocaust refugees across Europe.

[2] This expression was coined by Mariana Abrantes de Sousa and João Crisóstomo. The actual date of Sousa Mendes’s decision has been anecdotally placed on either June 16 or 17, 1940, following a reported three-day period of crisis during which he was in bed wrestling with his conscience. A recently discovered letter from Sousa Mendes to his son-in-law Silvério places him “in bed with a nervous breakdown” on June 13th; see De Winter Family Page. However, Sousa Mendes was already delivering visas in defiance of Circular 14 well before that period, as, for example, to the Wiznitzer and Ertag families. See: Wiznitzer Family Page and Ertag/Flaksbaum/Grunberg/Landesman/Untermans Family Page.

[3] The figure of 30,000 refugees (one third Jews, two thirds not) is impossible to confirm, but it can be traced to the 1940s. See Miguel Valle Ávila, “Was Lisbon Journalist ‘Onix’ Portugal’s Deep Throat? Aristides de Sousa Mendes Defended in the U.S. Press in 1946,” The Portuguese Tribune, October 1, 2013, p. 28. The figure is clearly in the correct order of magnitude: from a search on www.ancestry.com we can determine that 74,138 passengers traveled from Portugal to New York during the period from 1940 to 1942. To this number can be added an untold number of passengers assisted by Sousa Mendes who traveled to non-U. S. destinations, such as Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, and the United Kingdom. In addition, we need to count an estimated 10,000 stranded refugees who were never able to enter Portugal because of the action by the Salazar government to seal the French—Spanish border at Hendaye and Irun on June 24, 1940. See “Spain Halts Flow of War Refugees; Border Guards Hold up Most of Those Seeking Entrance,” The New York Times, June 25, 1940, p. 3; and “American Writers Escape Into Spain,” The New York Times, June 26, 1940, p.15. Some of these refugees, such as the Subotnik family were able to escape France through another exit route. Others, such as the Rajcyn family were forced to go into hiding in Nazi-occupied France and were ultimately deported and murdered.

[4] I coordinate the research team; past and present members include Ella Andriesse, Sylvain Bromberger, Angela Ferreira Campos, Paul Freudman, Jane Friedman, Catherine Gaulmier, Marie Gomes, Joan Halperin, Paula Kashtan, Monique Rubens Krohn, Linda Mendes, Harry Oesterreicher, Della Peretti, Jackie Schwarz, João Schwarz da Silva, and Daniel Subotnik.

[5] About half of the visa recipient families we have contacted had never heard the name of Aristides de Sousa Mendes and had erroneously believed that they owed their safety and freedom to the Salazar regime.

[6] Kent’s comments introduced the event Reflections on a Righteous Man (May 12, 2011, Center for Jewish History, New York), which featured a conversation between Dr. Mordecai Paldiel, former Director of the Department for the Righteous at Yad Vashem, and Sebastian Mendes, Professor of Art at Western Washington University and grandson of Aristides de Sousa Mendes.

My father and brothet went from antwert to lisbon in1942

Can you provide any further information? Are you sure that 1942 is the date they left Antwerp? Or is that the date they left Lisbon? What are their full names and dates of birth? Do their wartime passports survive? Sousa Mendes was no longer granting visas after June 23 or 24, 1940, as he was stripped of his functions and summoned to Portugal to stand trial.

Hello,

I wonder if you are aware that the JDC Archives in Jerusalem have a series of record originating from the JDC office in Lisbon during the war?

Regards,

Yoram Mayorek

Thank you. We have used the microfilmed JDC Lisbon files at the YIVO archives in New York. I wonder if it’s the same collection? Does the Jerusalem archive have originals or microfilms?

Embaixador de Portugal trava homenagem a Aristides de Sousa Mendes

Judeus de Buenos Aires descontentes com a decisão do diplomata. Neto de Sousa Mendes classifica esta atitude de “fascista”. E diz que Silveira Borges “deveria cessar funções”

MÁRCIO RESENDE, CORRESPONDENTE NA ARGENTINA

Dia 26 de junho, 11h30. Praça de Portugal, bairro Belgrano, Buenos Aires, Argentina. Ansiedade, memória, emoção. A Câmara Municipal presta uma homenagem histórica a Aristides de Sousa Mendes pela valentia de salvar mais de 30 mil vidas (entre 16 e 23 de junho de 1940) ao conceder vistos, desobedecendo às ordens do ditador Salazar.

Exatamente 75 anos depois, além de uma placa de homenagem, é plantada uma oliveira a partir de um galho da que Jorge Bergoglio, hoje Papa Francisco, então cardeal de Buenos Aires, plantou na Praça de Maio em louvor aos “Justos entre as Nações” — título que descreve aqueles que arriscaram as suas vidas durante o Holocausto para salvar as de perseguidos pelo nazismo. Assistem membros da comunidade judaica na capital argentina, a maior de toda a América Latina, alguns descendentes daqueles que Sousa Mendes salvou e que têm o português como herói.

Tudo muito bonito se não fosse apenas ficção: três dias antes da homenagem, com tudo pronto, a cerimónia do dia 26 foi cancelada ou, em linguagem política, suspensa. O motivo: uma carta do embaixador português na Argentina, Henrique Silveira Borges, a Lía Rueda, presidente da Comissão de Cultura da Câmara de Buenos Aires em 19 de junho. Na carta, o embaixador português argumenta que “infelizmente, a Embaixada não teve conhecimento prévio da iniciativa. O que me surpreendeu”, destacou o embaixador.

O ato de homenagem a Sousa Mendes tinha o apoio de diversas instituições dentro e fora da Argentina: Fundação Sousa Mendes, Delegação de Associações Israelitas Argentinas (DAIA), Centro Comunitário Sergio Karakachoff, Observatório Internacional dos Direitos Humanos, Museu do Holocausto em Buenos Aires, as embaixadas de França, Alemanha e Israel, Legislatura de Buenos Aires e até do Instituto Camões.

“O único apoio que faltou foi justamente o da Embaixada de Portugal. Aquela que deveria ter apoiado com mais ênfase, disse que não com o seu silêncio. Primeiro não respondeu; depois fez gestões para proibir o ato”, explica Victor Lopes, o português autor do projeto. Lopes tinha a autorização de João Correa, diretor do filme “O Cônsul de Bordéus” (a ser transmitido no Museu do Holocausto na semana seguinte), que, em novembro passado, com o apoio da Fundação Sousa Mendes, apresentara o projeto de uma placa de homenagem na Praça Portugal na autarquia.

De acordo com e-mails a que o Expresso teve acesso, Lopes escreveu ao embaixador Silveira Borges em 21 de janeiro e em 16 de março para lhe pedir apoio institucional. Nunca obteve resposta.

“ATITUDE FASCISTA”, DIZ NETO DE SOUSA MENDES

Contactado pelo Expresso, o embaixador começou por dizer não se lembrar se viu os e-mails. Mas depois demonstrou conhecer o conteúdo das mensagens: “Tanto quanto me lembro, nesses e-mails não havia qualquer descrição sobre os contornos concretos da iniciativa da homenagem. Diziam respeito a um projeto que seria submetido à Câmara de Buenos Aires”, diz. “Soubemos que estava em preparação uma homenagem, mas não tínhamos sequer sido consultados sobre a data ou sobre a forma”, escusa-se. “Uma coisa é o objetivo do projeto de dar um enquadramento institucional à homenagem. Outra coisa são os detalhes da homenagem que só soube quando recebi o convite quatro dias antes”, defende-se.

O embaixador admite que, embora não tenha respondido aos e-mails, entrou em contacto com a Câmara de Buenos Aires em fevereiro “para saber dos contornos do projeto”. Mas não entrou em contacto com o autor do projeto: “Esse senhor é quem tem de andar à minha procura. Não sou eu quem deve andar à procura dele”, justifica. E alega que “os e-mails estavam em espanhol quando um cidadão português deveria dirigir-se à sua Embaixada em português”. “Não é avisar de que vai fazer as coisas e depois pedir o patrocínio. O procedimento correto é falar em primeiro lugar com a Embaixada. E nós preparamos o projeto que se apresenta à Câmara através da Embaixada. A Embaixada não pode ser confrontada com um facto consumado”, argumenta. Ele próprio tentou, em vão, homenagear Sousa Mendes através do MNE argentino.

A Fundação Sousa Mendes, sediada nos EUA, emitiu um comunicado no qual destaca que “a Argentina foi um destino importante para alguns dos destinatários dos vistos de Sousa Mendes”. “Lamentamos saber que o evento foi cancelado. Confiamos que os beneficiários e admiradores de Sousa Mendes na Argentina possam unir-se para organizar um novo evento pelos 75 anos”, assinam o neto Gerald Mendes, presidente do Conselho, e Olivia Mattis, presidente da Fundação.

De Portugal, a título pessoal, o neto António de Moncada Sousa Mendes considera que “a atitude do embaixador português na Argentina é uma forma aberta de autoritarismo, de falta de respeito pelos cidadãos portugueses e pela História de Portugal”. “Essa atitude é fascista. É inaceitável o boicote desse senhor que deveria cessar funções”, sentenciou.

http://expresso.sapo.pt/sociedade/2015-08-15-Embaixador-de-Portugal-trava-homenagem-a-Aristides–de-Sousa-Mendes

The listing of “Leon Moed,Architect” is incorrect. It should be “David Moed,architect”

Documentary about the life of Aristides de Sousa Mendes

“Aristides was a man like any other simply that one of these crosses that knows not to put life in reacted like most” gets us saying Victor Lopes, an Argentine with Portuguese nationality who confesses “as some Portuguese give me shame and which I apologize to the whole world, there are also others such as Aristides de Sousa Mendes, who is the pride of a modern and vigorous Portugal that respects human rights and rejects any authoritarianism and dictatorship. ”

Sousa Mendes is one of four declared Portuguese “Righteous Among the Nations” for saving thousands of people persecuted by the Nazis during the Holocaust, while the Argentine film the documentary in Buenos Aires, the President of Portugal Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa Announces New York that will condecorar the Aristides de Sousa Mendes with “Grand Cross of the Order of Freedom” and acknowledges that “today you owe Aristides much more than we knew before.”

“One is not holy to be chosen by the gods, but, if it is chosen by the Gods to be holy.” Repeat Victor Lopes to signify the Consul’s humanitarian work of Portugal in Burdeus who signed 30,000 visas in just seven days disobeying the dictator Portuguese António de Oliveira Salazar, when the Nazis invadian France in cruel times 1940, “To Aristides had been easy vacate with the army or the police the grounds of the embassy at that moment filled with men, women and children persecuted looking for un safe conduct that led them to the port of Lisbon without Aristides embargo did not …. Sousa Mendes did not call the German troops. … what would I do? …. what would you do? what would our current Ambassadors of Portugal around the world? “.

It is the eternal conflict generated between “the duty and conscience not always agree themselves” says Lopes, as reminds us that soldier of the work of Javier Cercas that pudendal kill a Sanchez Mazas helpless decided not to do during the tragedy of Spanish Civil war

Portugal was a dictatorship for over forty years and untangle the web of complicidades with hundreds, thousands of professionals and leaders formed intolerance will take a long time to know to succeed in countries that experienced authoritarian regimes despite the efforts and goodwill that current leaders and new democratic generations do.

Take the American public of the screen the story of Sousa Mendes is one of the director’s goals with a team in Argentine universities cinema under the guidance of Paula Fossatti and Ramiro Klement, with the actors Melissa Zwanck y Nahuel Vec, Lopes will dock “the your grain of sand “to those who have already been doing for a long time in many parts of the world, family, friends and fervent followers of the cause Sousa Mendes.

The premiere of the documentary “Aristides good man” is scheduled for the end of the year and will be held at the International Festival of Human Rights, although Victor Lopes acknowledges that the proposal made a good reception because it-of a history practically unknown and still arouses certain controversy in the most conservative sectors of Portuguese society.

I heard about from my mother, her grandmother and grandfather were from Poland and escape to Bolivia and burn all Jewish document coz are afraid to get send back to there.

Unfortunately we can prove, to be honest, I would like to get notice from they history, prove from who Am I. By the way, my mom burn in 03/12/1944 in Bolivia and 18 years latter move to Brazil. I’m sure my sure name has some European history.